It took a little longer than expected, but the delayed US inflation figure for October came in just slightly below expectations. That means that, by the time this column is published, the Federal Reserve will have cut interest rates by another quarter point, and—unless something strange happens—another quarter point cut will follow in December.

One of the most important lessons I learned during and after the pandemic is that when it comes to central banks, you should only look at what they actually do, not what they say. When inflation skyrocketed, central bankers, including Fed Chair Jay Powell and ECB President Christine Lagarde, twisted themselves into absurd knots to systematically avoid raising rates. Christine will go down in history as the head of the ECB who stubbornly insisted that soaring prices were merely “temporary,” even with inflation at 8 percent, while Jay conjured up a series of arbitrary inflation metrics to hide behind that very same message.

What strikes me is how rarely the average economist or market analyst refers back to this period. They all act as if it was just an anomaly, and that monetary policy is now back to business as usual. It reminds me a bit of a goldfish—after one lap around the bowl, it’s already forgotten that it’s been there before.

Strange metrics

I’m not as good at forgetting. So when the inflation data are released—this time delayed by the ongoing US government shutdown, another oddity that tends to happen more often under Trump—I’m extra alert.

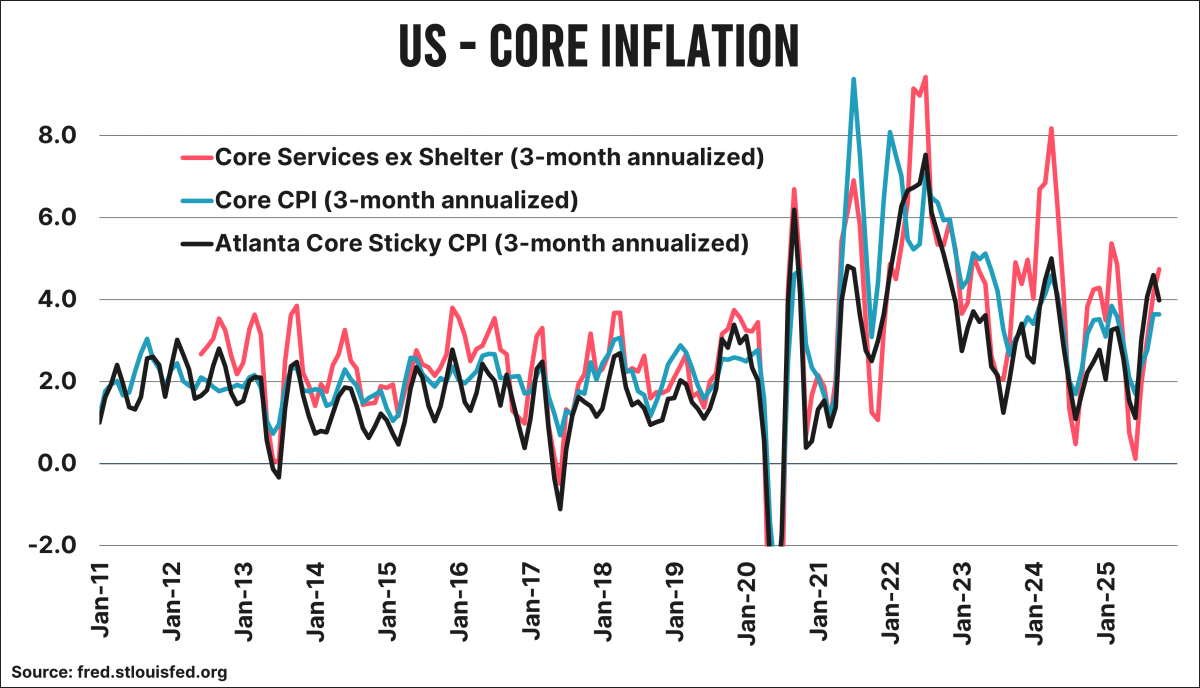

When US inflation shot to the moon, Powell treated us to a range of supposedly “better” inflation measures, all intended to emphasize the temporary nature of those massive price increases. These included the three-month annualized core inflation excluding shelter, the median price increase, and the so-called “sticky prices” index for goods with less flexible pricing.

I made a neat table of all these measures back then, just to see whether the numbers would finally move Powell and his colleagues to act. And because I don’t forget easily, I still keep an eye on those peculiar inflation metrics that were suddenly pushed to the forefront—first to justify doing nothing, and later to explain why rates were raised only gradually, long after the Federal Reserve had fallen miles behind the curve.

Here are a few of those figures:

- three-month annualized core inflation excluding shelter: 4.3 percent

- three-month annualized core inflation excluding housing: 4.3 percent

- three-month annualized core inflation for sticky prices excluding shelter: 4.0 percent

For context, the reported headline and core inflation rates in October were 3.0 percent—enough for a Friday celebration on the stock markets. But honestly, those figures aren’t even close to the Fed’s inflation target. Has Powell mentioned that lately?

Naïve

Is it strange that I find investors, economists, and so-called market experts naïve (to put it mildly) when they share their interpretations of the latest inflation data? Is it odd to suggest that the Fed hasn’t really been watching inflation for years, but is mostly focused on financial system liquidity (refinancing rules everything) and debt sustainability?

With my “investing in scarcity” fund, I’m often dismissed as a conspiracy nut—and that’s fine—but you can’t deny that something doesn’t add up. Barely three years ago, the Fed and other central banks opened a giant bag of tricks to convince us everything was fine. The fact that those same tricks still show that it isn’t seems conveniently ignored.

I do get why, though. If you’re heavily invested in equities, more rate cuts are, of course, the best thing that could happen.

If I were a journalist at Lagarde’s or Powell’s press conferences, I’d know exactly what I’d ask.

Jeroen Blokland analyzes striking, up-to-date charts on financial markets and the macro economy. He is also the manager of the Blokland Smart Multi-Asset Fund, which invests in equities, gold, and bitcoin.