What impact will AI have on the number of jobs, efficiency, and profits of publicly traded companies? It is important to distinguish between the short and the long term.

It was increasingly surprising that financial markets managed, with great perseverance and resilience, to climb higher despite grim geopolitical developments. It almost seemed as if the stock markets had once fallen into a cauldron of magic potion and thus possessed supernatural powers.

The explanation for this sturdy performance is, however, more down-to-earth. On one hand, US corporate earnings reported for the second quarter of 2025 provide a solid buffer that absorbs the impact of bad political news. Eighty percent of companies posted better-than-expected results, and upward revisions for the coming quarters were especially well received.

The second factor behind the stock markets’ sturdy behavior is the rock-solid conviction that the AI revolution will support further corporate profit growth and, thanks to a giant leap in productivity, accelerate it even more.

This belief was reinforced just days ago by a Morgan Stanley study from Stephen Byrd. Based on a few plausible assumptions, the study projects annual cost savings of nearly one trillion dollars for the 500 largest US companies once AI applications reach cruising speed. This assumption easily translates into higher stock valuations, both for companies supplying AI tools and those that make intensive use of them.

Efficiency gains

These efficiency gains are mainly driven by expected reductions in personnel costs. Administrative jobs with a highly repetitive nature or tasks with relatively simple decision structures are easy prey for generic AI applications.

Morgan Stanley even suggests that 90 percent of employment will be directly or indirectly affected by the coming wave of AI applications. Only jobs with a predominantly physical component or tasks that must adapt to rapidly changing environments are under less pressure.

This evolution will unfold gradually but destroy many jobs, particularly in administrative activities. In past automation waves, it was mainly manual, executional work that robots replaced. The loss of jobs is partly offset by newly created employment, but these tend to be fewer in number and require higher qualifications.

The main positive factor comes from the fact that goods and services can be produced more efficiently, appealing to a broader consumer base. As a result, production volumes rise to meet demand, and employment increases again (economists call this the Jevons effect).

A side effect—see research by economists Acemoglu and Restrepo—of the automation wave that pushed industry toward higher efficiency is downward pressure on wages. This explains why wages make up a shrinking share of GDP and why wage inflation has remained limited despite economic growth.

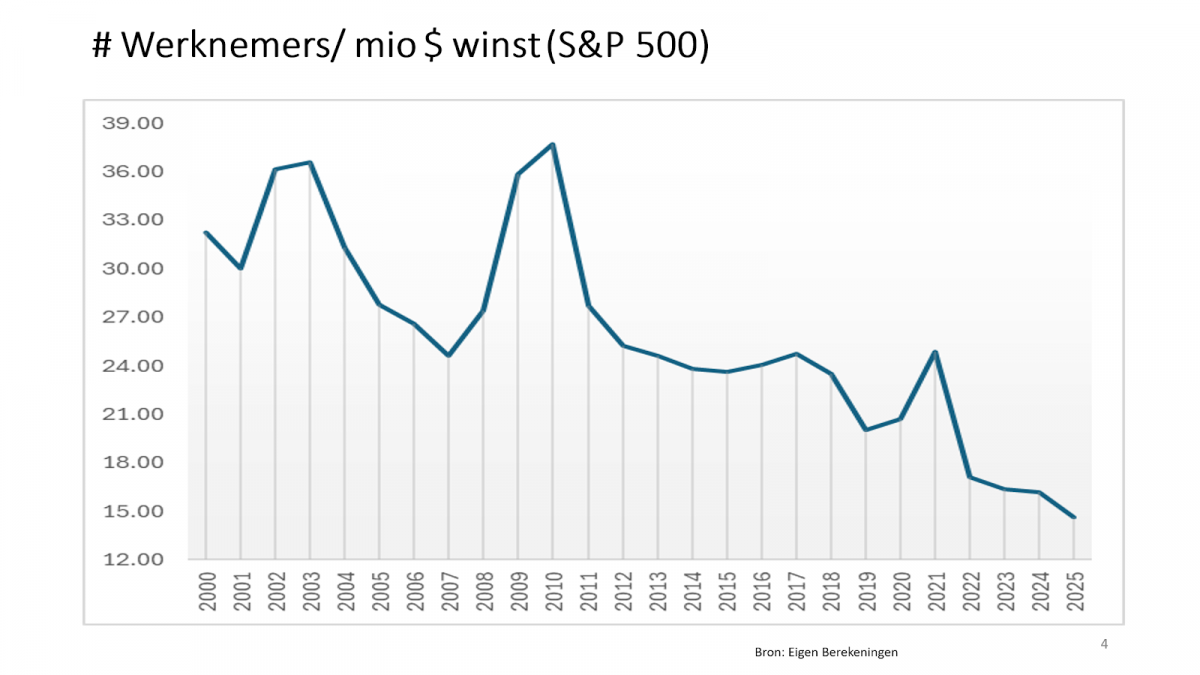

Illustrative is the evolution of the ratio of the number of employees per million dollars of net corporate profit over the past 20 years. I calculate this for the 500 largest US companies.

Chart 1: evolution of the ratio of employees per million dollars of profit

Amara’s law

But Amara’s law—named after American futurist Roy Amara—serves as an important warning today as well. It means we tend to overestimate the short-term effects of technology and underestimate its long-term impact. Overestimation leads to financial bubbles; underestimation causes missed opportunities.

So far, generic AI applications deliver much less than expected. A recent MIT study shows that 95 percent of companies using AI applications have seen no meaningful profit contribution. AI is used for research, discussions, or background information, but has not yet found its way into operational applications.

The main reason is that context changes so quickly that the learning curve of generic AI cannot keep pace. More advanced forms, such as adaptive AI, can make decisions more autonomously and adjust more quickly to a changing environment, but these applications are not yet widely available.

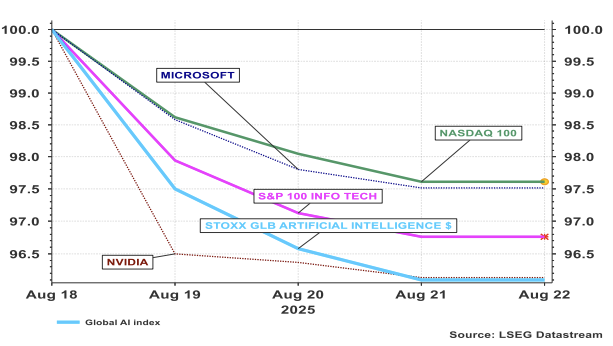

The findings of this now widely cited study wreaked havoc on technology stocks in recent days.

Chart 2: evolution of AI-related indices and stocks

Conclusion

The truth will lie somewhere in the middle between both viewpoints. One lesson is crystal clear: there is no room for naïve interpretations and speculative behavior, nor for doom thinking.

With a strong focus on specific subtasks, companies can indeed raise profit levels substantially through advanced AI efforts, but so far this has only applied to 5 percent of the firms studied. In every case, it required external, highly dedicated expertise. AI is therefore not for dabblers.

Stefan Duchateau is professor and columnist at Investment Officer.