For the average institutional investor, the appeal of lottery-like stocks—shares with a low price, high potential returns, and extreme volatility—is a mystery. But poorer investors simply reason very differently.

An institutional investor looks at the spreadsheets, calculates the Sharpe ratio, and immediately concludes: this is financial suicide. And that is true. Stocks (and even crypto tokens) with extremely high volatility, a low nominal price, and enormous skewness in returns deliver, on average, dismal performance.

Yet retail investors keep buying them. From penny stocks in the nineteen nineties to today’s Dogecoins and memecoins. Has the little guy gone mad? Or are we missing something?

Lessons from the past

The answer lies, surprisingly enough, in the archives of the Dutch tax authority. Together with my co-author Amaury De Vicq, I studied the effects of a unique historical experiment: the ban on the state lottery and other games of chance in the Netherlands. What did we find? The urge to gamble did not disappear; it shifted. And that shift teaches us a crucial lesson about how we should build portfolios today for different types of clients.

A brief history lesson: in 1905, the Dutch government decided to protect citizens from their appetite for gambling. Traditional lotteries were banned. But there was a loophole: so-called lottery bonds remained legal. These were bonds that paid a safe interest rate (the loan), combined with a periodic draw in which the holder had a chance to win an astronomical cash prize (the lottery).

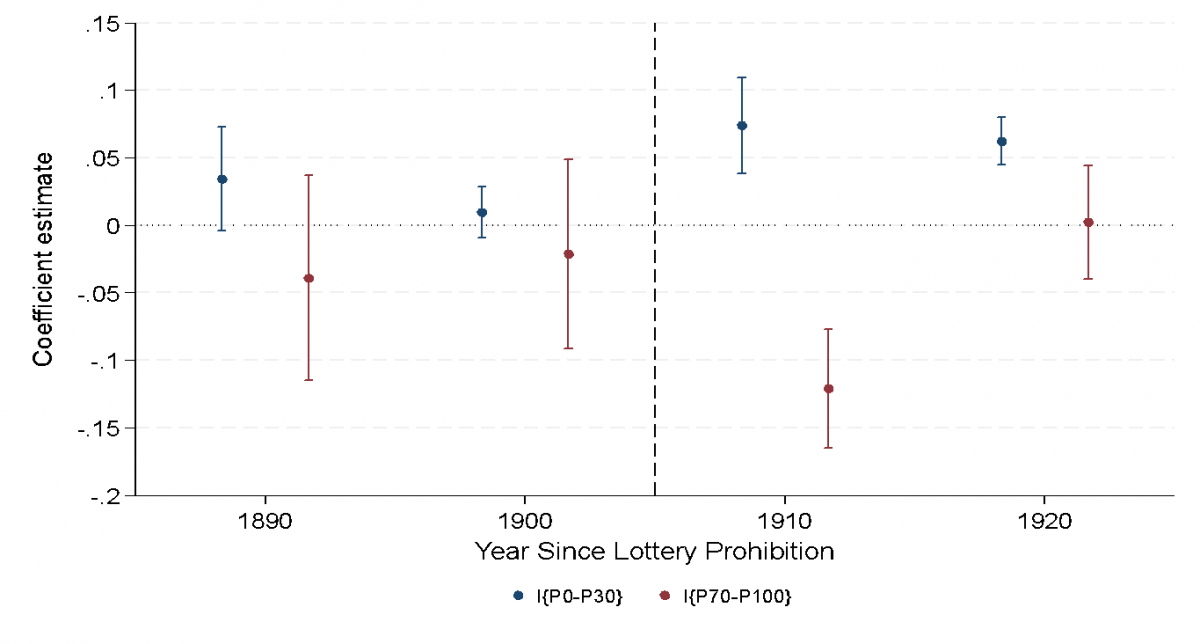

Our analysis of thousands of inheritance records reveals a fascinating pattern. After the ban, wealthy investors dumped these bonds en masse. For affluent investors, the fun was apparently gone, or they found more efficient ways to build wealth. Less wealthy citizens—those who would normally pin their hopes on a lottery ticket—did the opposite. They accumulated these bonds.

Figure: the percentage of lottery bonds in a portfolio for poor (blue) or wealthy (red) investors

Moonshot

This is where aspirational utility theory comes in. The key insight is that risk feels different when you have little to lose. For an institutional investor, a 7 percent annual return is excellent; thanks to compounding, wealth doubles every ten years. But for someone with limited savings, a 7 percent return changes nothing about their social status. They remain, relatively speaking, poor.

The only way for this investor to escape their social stratum is a moonshot. A small chance of a life-changing payoff outweighs the certainty of a modest loss. This explains the modern obsession with the lower end of the crypto market. Not (just) established bitcoin, but obscure memecoins trading for a fraction of a cent. Volatility is not a bug; it is a feature. It is a digital state lottery.

What the financial sector can do

As a wealth manager, you can do two things. You can shake your head and watch retail investors burn their money in these modern lotteries. That is the easy path. Or you can learn from the Dutch government in 1905. Lottery bonds were, perhaps unintentionally, a brilliant financial product. They channeled an inevitable urge to gamble into an instrument that simultaneously encouraged saving. The principal was safe, the interest was real, but the dream stayed alive.

Today, we see this structure reflected in prize-linked savings accounts, popular in countries like the UK and the US, but still underappreciated in Europe. The principle is simple: instead of interest, savers receive lottery tickets for a cash prize. It satisfies the hunger for skewness—the chance of that one big win—without eroding wealth.

Here lies an opportunity for the financial sector. Not every client benefits from the same index mix. For the “vulnerable investor,” or the younger generation dreaming of rapid wealth, simply preaching rationality is talking past them. Their rationality is different from yours. They are searching for hope.

Conclusion

It is up to us, as financial professionals, to package that hope into products that are not destructive. If we fail to offer safe alternatives that speak to these aspirations, retail investors will continue to seek salvation in the darkest corners of the crypto market.

History teaches us that you cannot ban the urge to gamble, but you can guide it. The lottery bond of 1905 was not a perfect investment, but it was a safe haven for dreamers. Perhaps it is time we reinvent that harbor.

Gertjan Verdickt is an assistant professor of finance at the University of Auckland and a columnist at Investment Officer.