So far this year, the euro has appreciated by no less than 13 percent against the US dollar. That drop in the dollar’s value — because that’s what it really is—was first explained as America discarding its “exceptionalism” under Trump.

Then came the narrative that a US recession was around the corner, fueled by the trade war, followed by talk that the Federal Reserve had folded and would push ahead with more rate cuts. Maybe all that’s true. But to me, the euro remains vastly overpriced — you just need to keep the right perspective.

Pressure valve

The eurozone is a rickety patchwork of wildly different countries that opted to adopt a currency built with structural flaws. That means that whenever there’s trouble within the bloc, the obvious pressure valve is nearly always the euro itself.

So when yet another French prime minister was forced to resign within just a few weeks—the latest in a long line—the euro dropped by about 0.5 percent. Realistically, it should’ve fallen at least 10 percent.

The weakest link

A few years ago, France took over the dubious honor of being the weakest link in the stitched-together collection of nations we call the eurozone—a title previously held by Italy. Make no mistake: Italy, alongside Greece, consistently tops the list of countries with the highest public debt as a percentage of GDP.

France, however, does even worse when it comes to putting its public finances in order. Politicians bicker endlessly about trimming social programs, reforming healthcare and other sectors, or abolishing public holidays—yet nothing ever gets done. In a country where the retirement age is 62, tinkering with the unsustainable welfare state is political suicide. Alongside fiscal instability, France is increasingly defined by political instability as well.

The spread

The market has a perfect mechanism to reflect fiscal and political troubles: the spread. The extra yield France must pay over supposedly safe German government bonds has widened and now sits near its highest level in years. Selling French bonds is investors’ way of saying they have little faith in France’s fiscal policy.

How do Dutch pension funds—which will start transitioning to the new pension system next year and are expected to sell large amounts of bonds—view this, I wonder? Maybe a question for a future column.

The mismatch

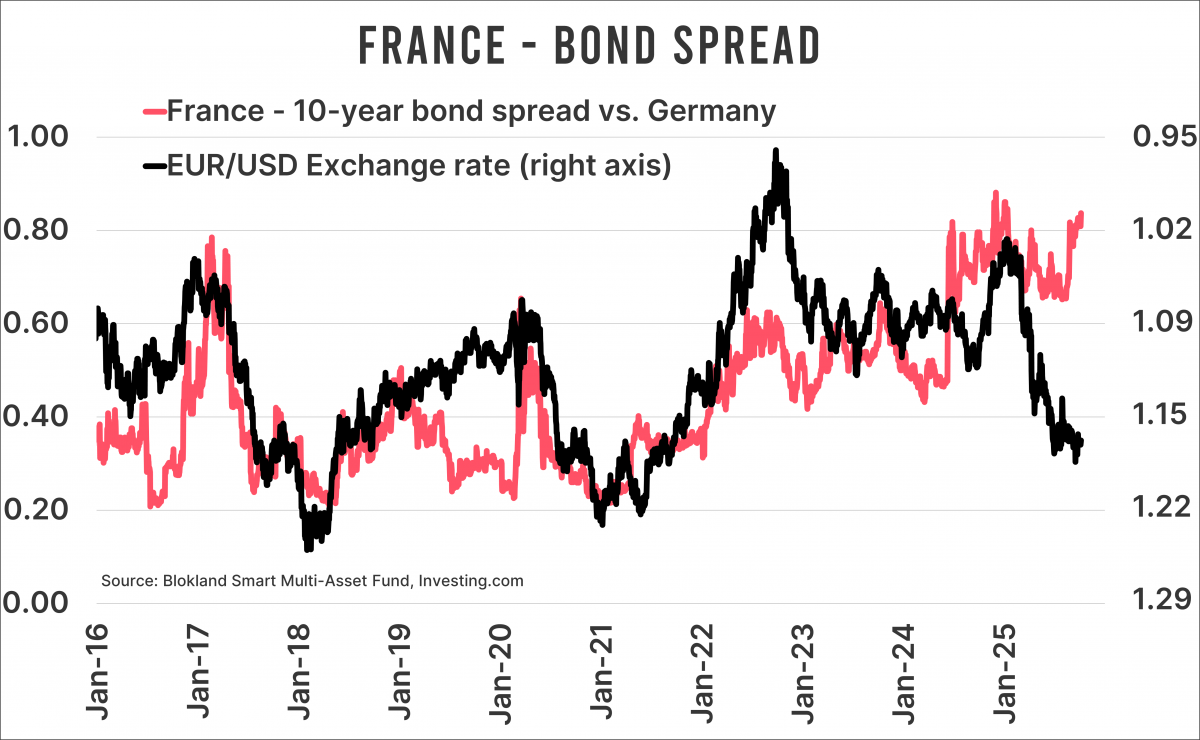

And what about the euro itself? The answer is simple: it usually moves in tandem with the French spread—except this time. The chart below shows that the euro and the French spread have actually been moving in opposite directions. In other words, when France must pay more because of fiscal chaos, the euro should be falling against the dollar.

That makes perfect sense, doesn’t it? Don’t get me wrong: the pressure on the dollar’s dominance and the Fed’s upcoming rate cuts certainly matter. But if the European debt crisis of nearly fifteen years ago taught us anything, it’s that when one country gets into trouble, the entire zone comes under strain. “Whatever it takes” was the only thing that kept it all together back then. That seems far more urgent to me than the idea that the dollar might lose its reserve-currency status—though, to be fair, the dollar’s foundations are definitely being chipped away at.

Looking at the chart, the euro really should be closer to 1.02, not 1.20. And what if the spread continues to widen in the coming weeks? Let’s not get ahead of ourselves — the fiscal outlook across the Atlantic isn’t exactly reassuring either.

Jeroen Blokland analyzes striking, topical charts on financial markets and macroeconomics. He also manages the Blokland Smart Multi-Asset Fund, which invests in equities, gold, and bitcoin.