No, I haven’t started a Chinese course. Unfortunately, because I think it would be quite useful these days.

The title of this column is the Chinese word for “mirage” or “illusion.” Hot air, in other words. Just like the impressive Chinese growth figure that was proudly announced this week.

Excellent

According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, the Chinese economy grew by as much as 4.8 percent in the third quarter of this year compared to the same period a year earlier. The same bureau says this provides a solid foundation for achieving the target of 5 percent GDP growth in 2025.

An excellent number, of course. The problem is, I have no idea where that growth is actually coming from. During the quarter, Chinese retail sales growth dropped to only 3 percent. Fixed asset investments shrank—something that has only happened once before, during the pandemic. Housing prices are falling faster again, and real estate investment remains, in a word, disastrous. Trade contributed positively to economic growth, as it does every quarter, but the surpluses were smaller than before.

Question marks

It makes you wonder where that reported growth really comes from. When you also consider the mild deflation—a phenomenon usually associated with contraction rather than overheated economies growing by nearly 5 percent—it’s hard to make the numbers add up.

To get a better sense of those beautiful growth figures, assuming they weren’t neatly written down out of thin air by a Chinese official, you need to look beyond the standard economic indicators. China is certainly not the only country where that’s necessary when GDP figures are released.

A massive pile

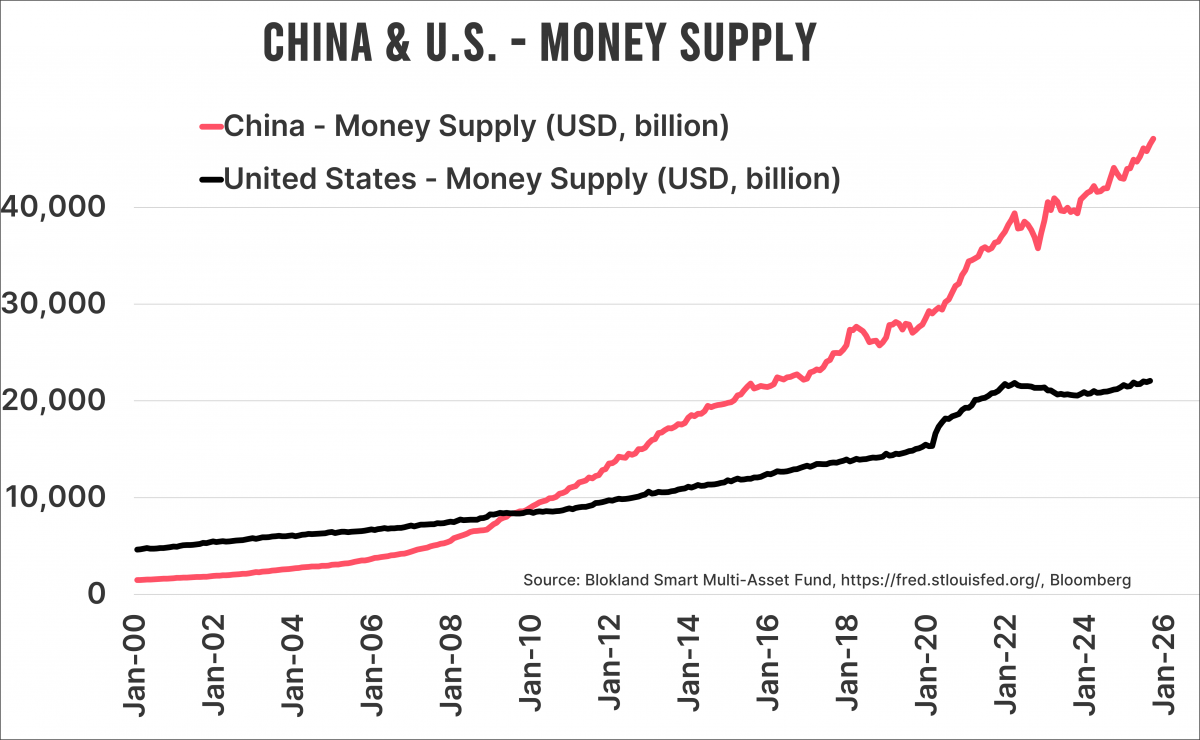

You don’t have to look far to see where China’s growth originates. It’s really no different than in any other aging economy. Below is a chart comparing the US and Chinese money supply. China’s money supply is more than twice that of the United States. Few people ever mention the extreme monetary expansion in the world’s second-largest economy. With that much new money, you can simply buy the growth you need.

Instead of showing the money pile, I could just as well have displayed a chart of China’s mountain of debt. Although still smaller in GDP terms than that of the United States, the pace at which Chinese debt is increasing is staggering. Moreover, the official debt figures are likely understated. Local governments in China owe trillions that don’t appear on the (central) government’s balance sheet. China is buying its growth—there’s no better way to put it.

A painful outlook

Why the Chinese government insists on maintaining a GDP growth target of 5 percent is beyond me. You don’t need to be an expert to do the math. China’s labor force is shrinking—a little now, by about 1 percent per year in a decade, and by as much as 2 percent per year in about thirty years. Based on the labor factor alone, China starts with negative growth. Add productivity growth of around 2.5 percent, in line with recent years, and you’ll never come close to that 5 percent. Even with an AI boom that doubles productivity growth (certainly not my base case), the target remains out of reach.

It’s remarkable how issues that so clearly don’t add up—quite literally, in this case—rarely receive the attention they deserve. The Chinese economy will not structurally grow by 5 percent per year. Period. Something I suspect they are well aware of in Washington. That could make for an interesting topic of conversation when Trump visits China in March, just after the new five-year plan is unveiled—no doubt again featuring 5 percent annual GDP growth as its headline goal.

Jeroen Blokland analyzes striking, timely charts on financial markets and macroeconomics. He also manages the Blokland Smart Multi-Asset Fund, which invests in stocks, gold, and bitcoin.