The accelerating growth of active ETFs is blurring the lines between active and passive management. Critics warn that it may be an old trap in a new disguise: funds that claim to be active but behave almost exactly like an index—the so-called closet trackers.

ETFs have now been around for 25 years in Europe, ever since Deutsche Börse launched the first index trackers in Frankfurt in 2000. For a long time, the product was synonymous with passive investing. But increasingly, ETFs are being used as vehicles for active management.

Interest in active ETFs is rising quickly. According to research firm ETFGI, active ETFs in Europe attracted 13.4 billion dollar in new capital during the first half of 2025—more than double the 5.1 billion dollar seen in the same period last year.

Active ETFs aren’t new—they’ve existed since 2011. But they’re now being used far more widely. According to Fidelity portfolio manager Ilia Chelomianski, this is because central banks are no longer steering the markets. “That’s why investors are turning to active management to gain control over risk in an environment of rising volatility and concentration risk.”

The rise of active ETFs raises a fundamental question: how active is “active” really? It’s a question that previously emerged in the active/passive debate with the term closet indexing, which gained broad attention following the influential 2006 study by Martijn Cremers and Antti Petajisto, How Active Is Your Fund Manager? A New Measure That Predicts Performance.

Now, three decades after the launch of the first ETF, the industry is discussing a new variant: the so-called “shy ETF”.

Passive versus active

Back to the purpose of active ETFs. According to Chelomianski, it often comes down to “locking in market beta.” He argued that the better approach is to use active ETFs to seek out alpha opportunities. “That way, you can take calculated risks.”

Aberdeen Investment defines active ETFs on its website as investment vehicles aiming for risk-adjusted returns that outperform their benchmark.

Head of ETF Distribution at J.P. Morgan Asset Management Benelux, explains that an active ETF can serve different objectives: “The primary focus isn’t always on generating alpha. Some active ETFs are designed to deliver income and aim for lower volatility and beta than the benchmark, rather than pursuing alpha.”

According to her, the confusion around the role of active ETFs stems from unrealistic expectations. “There’s a misconception that active ETFs must by definition be benchmark-agnostic with high tracking error. At J.P. Morgan Asset Management, our active ETFs follow different risk budgets, ranging from index-agnostic to index-aware. In the latter case, we actively manage positions through targeted over- and underweights in individual stocks, based on fundamental bottom-up analysis.”

Shy active ETF

Morningstar was the first to label ETFs that market themselves as active but barely deviate from their benchmarks as shy active. The Financial Times adopted the term and noted that few of these ETFs actually function as traditional stock pickers.

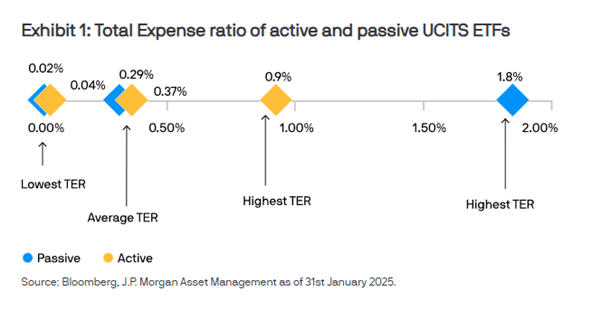

The criticism that active ETFs are more expensive than passive ones is partly valid: costs are slightly higher depending on the strategy, but still close to those of passive ETFs. They are generally cheaper than traditional actively managed funds.

Rootsaert emphasizes that fees should not erode returns. The goal of an active ETF is to outperform the benchmark and generate alpha, and its cost structure should not stand in the way. “At J.P. Morgan Asset Management, we use fundamental insights to generate alpha. Over the long term, that alpha should offset the fees and deliver additional return.”

“People often forget that with passive ETFs, you always get the benchmark return minus the annual cost,” says Rootsaert. “In volatile markets with wider spreads, such as EMD and high yield, there’s also more slippage. You track the benchmark, but rarely achieve exactly the same return.”

Pure passive investing

It doesn’t surprise Hendrik Meesman of Meesman Indexbeleggen that confusion around what counts as passive or active management keeps resurfacing. “The financial sector thrives on confusion because it benefits from active trading. Year after year, SPIVA and Morningstar studies show that active trading leads to poor investment outcomes.”

Despite all the talk in recent years about the rise of passive investing, Meesman said that’s only partly true. “Index investing has indeed grown, but most investors in index funds or ETFs are not really investing passively, because they fail to diversify globally,” he explained. “If you choose an ETF that tracks the AEX, you are deliberately opting to invest in just 25 Dutch companies, even though there are thousands of options globally.”

According to Meesman, there’s only one form of truly passive investing: investing in the entire market. By that, he means spreading investments as broadly as possible, accepting that you can’t predict the market, and simply aiming to capture the average return. “And almost no one is doing that,” Meesman concluded.