When everyone expects the same thing, it is time to think differently. A good example comes from Value Line, a company that makes stock market forecasts. They predict higher returns when valuations are low. Individual investors do exactly the opposite.

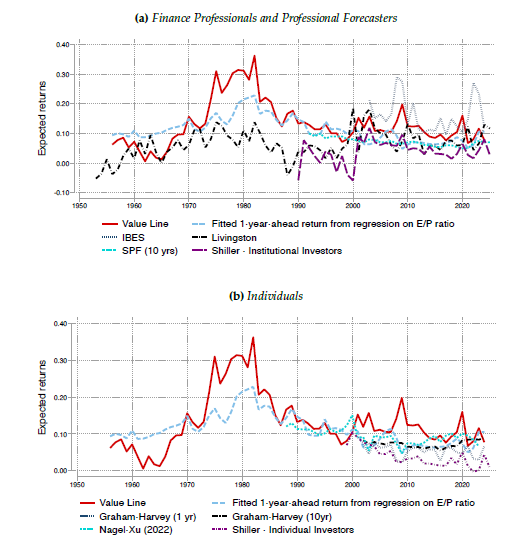

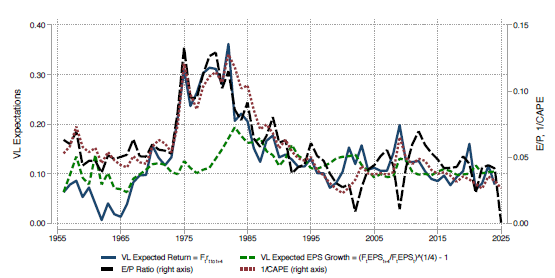

Seventy years of data reveals a fascinating pattern. Professional analysts at Value Line expect higher returns after market declines. Their forecasts correlate strongly with the price-earnings ratio and prove to have predictive value. Retail investors, by contrast, extrapolate: after rises they expect more rises, after declines more declines. Their expectations have no predictive value. In fact, they correlate negatively with future returns.

Figure 1: Expected returns over time

This gap is not accidental. It reflects a fundamental market dynamic: when investors become optimistic, prices rise. That forces professional parties to become more pessimistic—otherwise the market cannot clear. The result: their expectations move in opposite directions. When the difference is largest, trading volume explodes.

The implication? Consensus is suspect. When everyone is looking in the same direction, the best opportunities are often found in the opposite direction. Not because the crowd is by definition wrong, but because prices already reflect consensus.

This pattern repeats itself throughout history. Early 2009, after the financial crisis: Value Line predicted returns of 30 percent, while retail investors displayed flight behavior. The S&P500 then rose by 26 percent in twelve months. Late 1990’s, during the internet bubble: retail investors expected 20 percent returns, professionals were skeptical.

Figure 2: Valuation ratios, expected returns, and expected growth

Against the current

The art is not to go against the crowd for the sake of being contrarian. The art is to recognize when expectations become extreme. When optimism or pessimism has embedded itself in the collective psyche, valuations are often far from equilibrium.

What does this mean for institutional portfolio management? Three things:

- Have the courage to swim against the current when valuations justify it. Rebalancing works precisely because it is anti-consensus.

- Distrust market commentary that sounds too smooth: when a narrative is widely accepted, it is already in the price.

- Use sentiment as a contrarian indicator. Not as the sole input, but as a warning signal when expectations reflect extrapolative behavior.

The paradox of expectations is that they neutralize themselves. What everyone expects rarely happens—simply because everyone has already anticipated it. The greatest opportunities lie where expectations are most out of balance with fundamentals.

Indeed, seventy years of market history teaches us that sophistication pays. Not the sophistication of complex models, but the ability to recognize when the crowd chooses a direction. Then it is time to look the other way. The question is therefore not what the market will do. The question is what the market expects the market to do—and whether that expectation is sustainable.

Gertjan Verdickt is assistant professor of finance at the University of Auckland and columnist at Investment Officer.