In financial markets, 2026 will not only be a year of economic normalization, but also a test of the institutional fabric of US monetary policy. Renewed political polarization and the approaching expiration of central banker Jerome Powell’s term are creating a rare convergence of uncertainty for the period ahead.

For institutional investors who primarily rely on predictable risk premia and stable inflation paths, it is crucial to understand what is at stake. Thanks to new academic work, we now have a stronger analytical framework. And that framework, uncomfortably enough, applies remarkably well to the current political climate.

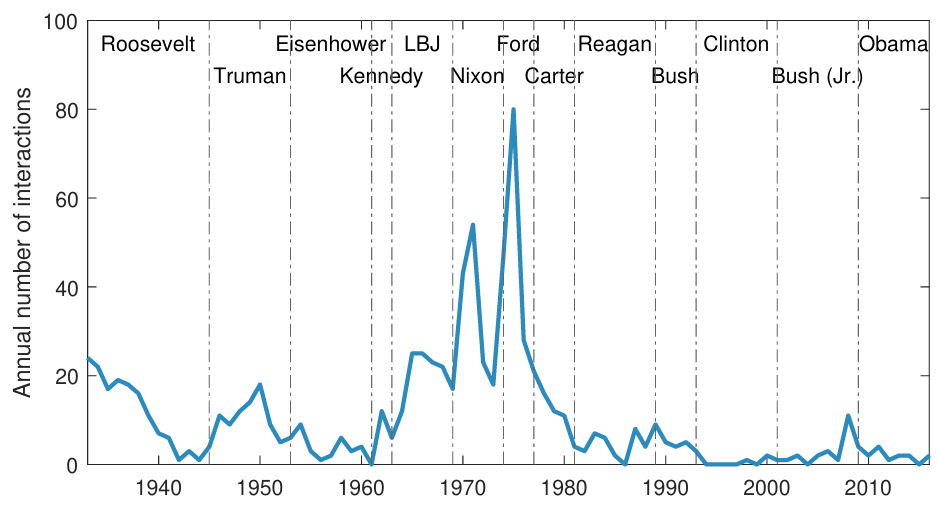

Figure: The number of interactions between the Fed chair and the US president

Thomas Drechsel (University of Maryland) reconstructs nearly a century of personal interactions between US presidents and Fed chairs, the heads of the central bank. His core finding is consistent:

- When presidents pressure the Fed, the price level rises sharply and persistently.

- The real economy barely responds.

- The effect on inflation expectations is large because this political pressure is publicly visible.

The classic example is Richard Nixon, who pushed Fed chair Arthur Burns in 1971 to cut interest rates in the run-up to his reelection. The outcome was a politically motivated rate cut that still explained a permanently higher price level more than a decade later.

Why this matters in 2026

Jerome Powell’s term expires in 2026. Trump has previously expressed strongly worded views on monetary policy and on Powell personally (“enemy,” “bonehead,” to name the most sympathetic ones), and insiders expect that this time he will choose a chair who is explicitly dovish, or at least politically loyal.

The names currently circulating, including Kevin Warsh, who nearly replaced Powell in 2017, illustrate that the risk of a less independent Fed is real. Warsh has previously stated publicly that the Fed has been too reactive and overly cautious, suggesting that he might be more willing to ease more quickly under political pressure.

Combine this with a Trump agenda that leans on fiscal expansion (think tariffs, tax cuts, industrial policy), and the contours of the risk become clear: a regime in which politically driven monetary easing structurally adds inflation.

This is exactly what Drechsel documents in earlier episodes. The transmission does not run through output or employment, but through expected inflation and the perception that the Fed is less willing to make painful choices.

Market implications: what institutional investors should consider

- Break-even inflation levels could structurally move higher.

- Rates: lower nominal levels in the short term, higher levels in the long term.

- Dollar regime: from safe asset to political asset?

- Equities: valuation volatility and sector rotation.

A politically driven easing bias supports nominal earnings growth, but valuation multiples become more sensitive to inflation expectations. When considering the theoretical impact on equities, the potential beneficiaries may include:

- financials,

- real assets,

- defensive value stocks.

Technology and duration-sensitive growth stocks, by contrast, become more vulnerable.

Conclusion

The institutional risk surrounding the Federal Reserve is an underappreciated variable in markets. Drechsel’s research shows that political pressure is both detectable and macro-relevant, and that its effect is primarily inflationary. The parallel with Nixon is no longer an academic anecdote, but a plausible scenario. Whether the next Fed chair is Kevin Warsh or another Trump-appointed candidate is far more than a personnel decision. It is a regime choice.

Gertjan Verdickt is assistant professor of finance at the University of Auckland and a columnist at Investment Officer.