A new year, a new round. Every year at the beginning of January, I once again look with amazement and confusion at the equity market outlooks from the major financial institutions. And especially at the projected returns, which are invariably clustered right around the long-term average. Because one thing you can be almost certain of is that those projections will not materialize.

Basing stock market forecasts on the long-term average return is an extremely poor “crystal ball strategy.” After all, the average return almost never occurs. You are far better off being that ridiculous raging optimist or a genuine permabear. Moreover, at least in my case, that commands far more respect than the “let’s-stick-nicely-close-to-the-average” forecasters.

The numbers at a glance

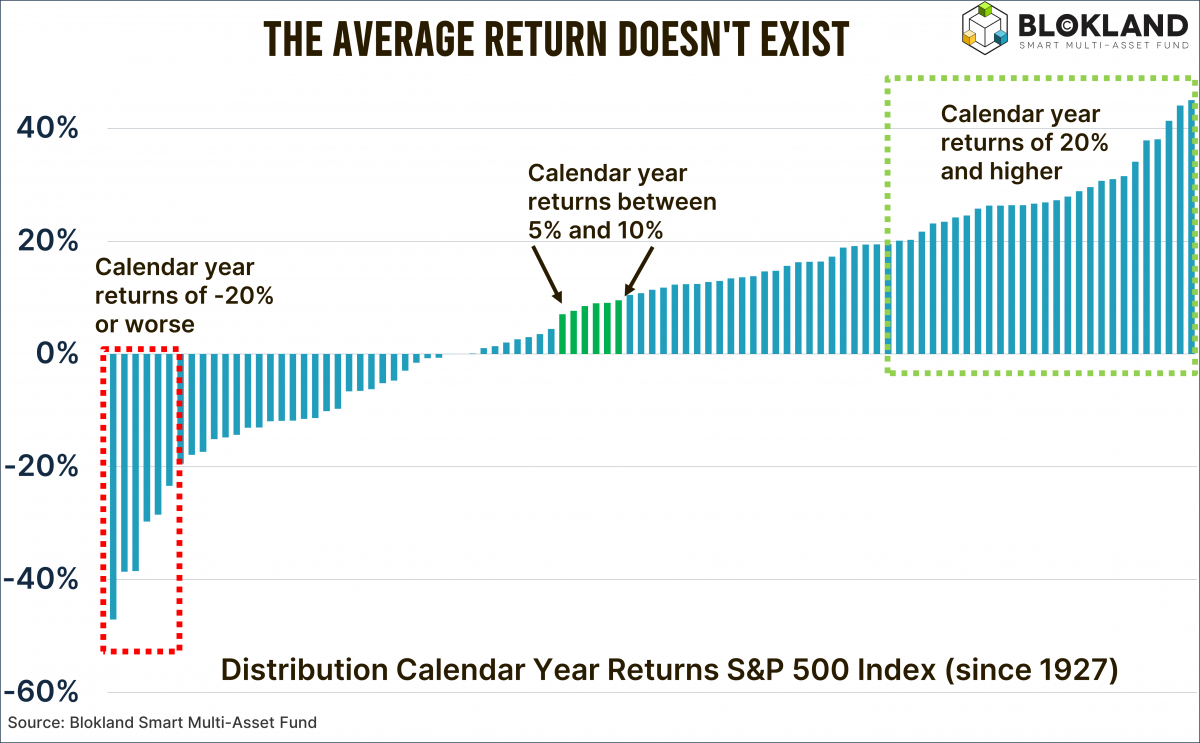

Since 1927, the (back-calculated) average annual return on the S&P500 index has been 8.1 percent. With only that number in mind, a forecast of, say, between 5 percent and 10 percent sounds very professional. But if you dig even slightly into the underlying data, you quickly see that the opposite is true. It mainly reflects a lack of historical return insight.

In the 97 calendar years since 1927, the return on the S&P500 index has fallen within that range only six times. You read that correctly: just six times. And in 2025, it was again not the case. The S&P500 delivered a return of 16.4 percent.

That paltry number of six means that, as a so-called market guru, you would have been right barely 6 percent of the time if you had rolled out that “uninformed” 5–10 percent forecast every year. That is not very impressive.

Choose extreme

A far better strategy would have been to predict every single year that equities would rise by at least 20 percent. In that case, you would have been right 28 times, a hit ratio of 29 percent. Yes: if you had been “crazy” enough to proclaim a return forecast of 20 percent or more every year, you would have been right in almost one out of three years. Your “forecasting skill” would have been five times better than that of someone who opted every year for a forecast between 5 percent and 10 percent.

But even if you had played the permabear every year, something some experts have made their trademark, you would not have underperformed the average huggers. Since 1927, the S&P500 index has fallen by 20 percent or more six times. Because it takes considerably more nerve to make such a potentially “career-limiting” forecast every year, I also consider permabears to be better forecasters than those huggers.

Once again, little historical awareness

This year as well, professional forecasters show that they have not read my column “The average does not exist”. The median return forecast from the 21 experts at the largest investment banks comes in at 9.4 percent. Admittedly, that is on the high side for this group, even deviating ever so slightly from the long-term average, but of course still neatly within the 5–10 percent window.

Eight of the 21 forecasters actually delivered an expectation between 5 percent and 10 percent. That is roughly 40 percent of the forecasters. For them, this implies a 94 percent probability (in 91 of the 97 years since 1927 the return fell elsewhere) of being wrong. Last year, that percentage was almost 50 percent, so perhaps a few have finally seen the forecasting light.

Although. Not a single market guru dared to put forward a return forecast of more than 20 percent. Not one. Even though, based on history, the probability of this happening is 29 percent. You would expect that, among 21 forecasts, a few experts would at least have glanced at the historical return distribution. Apparently not.

In addition, none of the surveyed investment experts predicted a negative return. From a group of 21 participants, that is perhaps even stranger, given that the probability that the return in any given calendar year is negative is almost one third. The lowest expected return for 2026 is plus 2.3 percent.

It remains astonishing how poorly informed forecasters are about the returns of the asset class they are supposed to understand.

More likely, they secretly do know this, but the pressure to avoid being an outlier is extremely strong. That fits perfectly with the picture that the institutions these forecasters work for also remain stuck in a world of nothing but equities and bonds. But that is a topic for another time.

Best wishes for 2026! May it be a great year.

Jeroen Blokland analyzes striking, topical charts on the financial markets and the macroeconomy. He is also the manager of the Blokland Smart Multi-Asset Fund, a fund that invests in equities, gold, and bitcoin.