It’s December, and so the focus is shifting to 2026. As always, this comes with a wave of outlooks that are, unfortunately, often already partly outdated by the time the new year begins. Still, a dynamic is now unfolding that could lead to quite a bit of fireworks next year.

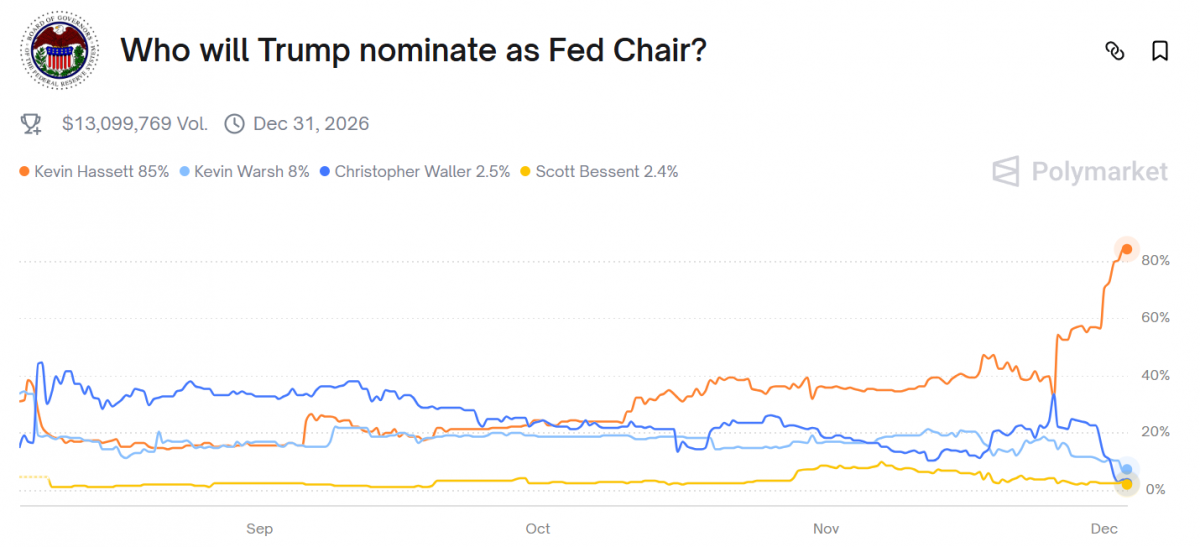

Trump’s little performance in which he told journalists that he will announce the successor to Fed Chair Powell early next year (calling him a “stubborn ox” while he was at it) was certainly entertaining. In his remarks, he also made sure to praise Kevin Hassett, who according to Polymarket now has an 85 percent chance of being appointed.

It is widely known that Hassett is firmly in the Trump camp and therefore openly advocates significantly lower Fed rates. The days are gone when central bankers were, at least in appearance, selected for their reputation and independence. This fits perfectly within a regime of fiscal dominance, in which monetary policy ultimately has to give way to fiscal (mis)management. If Hassett gets the job, expect plenty of rate cuts, regardless of what inflation does

Seatbelts on

That brings me to the central point of this column. Nice as they may be, all those point estimates for next year’s economic growth or projections that equities will rise 5, 6, or 7 percent (analysts on average remain suspiciously close to the long-term return on equities), the bigger picture suggests we could be heading for a tumultuous year.

Next year, the Federal Reserve will begin expanding its balance sheet again. In other words, market liquidity will increase. This effect will be amplified by the Enhanced Supplementary Leverage Ratio, which is estimated to free up roughly one thousand billion dollar in repo capacity. Put simply, banks will have far more room to expand their balance sheets and strengthen their intermediary role through market making, liquidity provision, and so on. Naturally, this will involve more US Treasury securities being used as collateral.

That wave of liquidity could, especially if Hassett aggressively cuts rates, immediately push inflation expectations higher and thereby exert strong upward pressure on interest rates. That would largely undo the work of the newly appointed Fed chair, as rising long-term rates would still slow the economy. This could force the central bank to fire up the money printers again and, through quantitative easing or some derivative of it, push long-term rates back down. Such bond purchases tend to flow in one direction: toward the most liquidity-sensitive asset classes.

Volatility in the making?

It has become a cliché appearing in nearly every outlook: rising markets with a chance of volatility. If you are wrong, you can always blame the volatility; investors do not like it anyway.

The way I see it, much of that volatility will be concentrated in the bond market. Especially if the prospect of higher rates (even if they are, in my view, being capped) starts to hit the economy. That would mean that all those fragile budget deficits could once again end up much higher than expected.

If this coincides with waves of liquidity and inflationary pressure, it could become the catalyst for an even wider gap between real, scarce asset classes on the one hand and rate-sensitive categories on the other.

Political unrest

Unfortunately, it does not stop there. If a new inflation wave truly emerges and the purchasing power of the average American—and citizens elsewhere—erodes further, social and political unrest will intensify as well. After everything we have witnessed in recent years, that is hardly a comforting prospect.

Now what?

The final question that comes to mind is whether, if this scenario of markets with two faces (equities, gold, bitcoin, and so on rising while bonds, private debt, and savings decline) plays out, traditional investors will still dare to cling to their 60/40 principle. Even Vanguard—though owned by its own funds and thus indirectly by its clients—eventually gave in, after years of going against the wishes of those same clients, and now offers bitcoin funds. But I have my doubts whether this is truly about accommodating client demand or whether it is primarily about revenue.

Jeroen Blokland analyzes striking, current charts on financial markets and the macroeconomy. He is also manager of the Blokland Smart Multi-Asset Fund, a fund that invests in equities, gold, and bitcoin.