Almost daily, I find myself amazed at how people simply refuse to see certain things. On the street, in politics, but also in the financial markets.

How often investors choose to systematically ignore the colossal elephant in the room is beyond counting. Even when trusted friends confirm the presence of that elephant, they stare straight in the other direction. And this column, too, will probably not reach their eyes.

Interest rate rocket

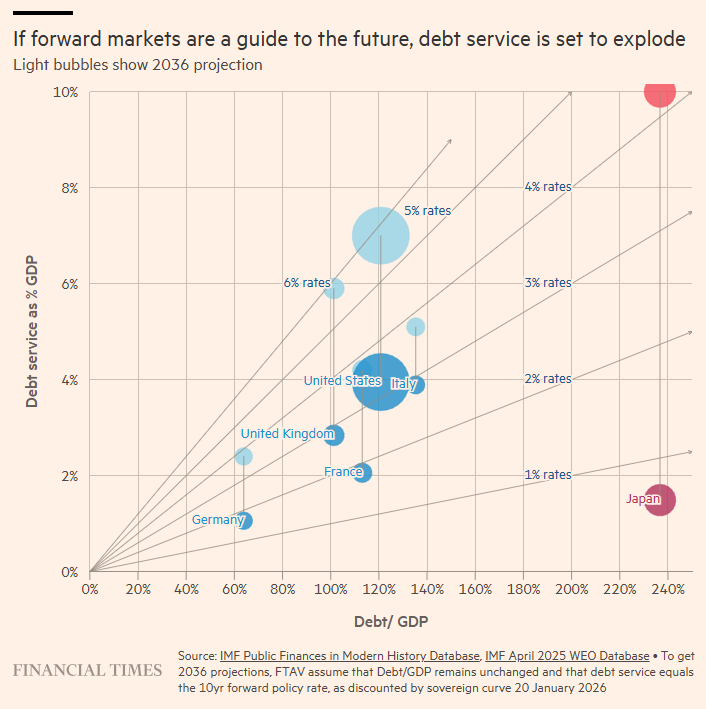

Enter Toby Nangle, journalist at the Financial Times and known for the popular blog FT Alphaville. After the interest rate explosion in the Japanese bond market, he took to his pen to lay out in detail the unsustainability of high interest rates. The most important chart from Nangle’s contribution is shown below.

It shows the size of debt as a percentage of GDP of the G7 countries (horizontal axis), plotted against the interest costs on that debt, also expressed as a percentage of GDP (vertical axis). The dark-colored dots reflect the current situation. Japan is shown in (dark) red, the other countries in (dark) blue. For example, the United States currently pays interest equal to roughly 4 percent of GDP on a debt of around 120 percent of GDP.

To make the impact of higher interest rates visible, Nangle then runs the following scenario: interest costs as a percentage of GDP in 2036, under the assumptions that 1) the current debt mountain does not increase further and 2) that entire debt is refinanced at the then-prevailing short-term interest rate (policy rate), as the market currently expects for ten years from now.

Perhaps you have already, quite rightly, gotten stuck on the assumption that the debts of these G7 countries will not increase further. For convenience, park that thought for a moment. The light blue dots, and in Japan’s case the light red ones, show the outcomes. For the United States, annual interest costs in this scenario rise from 4 percent to no less than 7 percent of GDP. In other words: without spending even a single second thinking about future budget discipline, America is automatically staring at an additional budget deficit of 3 percent of GDP per year. Exactly the percentage that, according to the Maastricht Treaty, the total budget deficit is allowed to be at most.

The land of rising burdens

Now look at the red dots. Japan, with its mega-debt, goes from interest costs of less than 2 percent of GDP, the direct result of eight years of “yield curve control,” to a staggering 10 percent in annual interest costs. What?

Even if you have 0 percent understanding of how our economic growth model works, if you do not know that the debt mountain will almost certainly continue to grow, or if you have not read my book in which I show that old, aging economies actually need structural budget surpluses to maintain their standard of living, you can effortlessly conclude that this is simply unsustainable.

What’s so hard about the choice?

In 1981, economists Thomas Sargent (a later Nobel Prize winner) and Neil Wallace published an extremely influential paper that is more relevant today than ever: Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic.

Their core thesis: when governments run structural budget deficits and finance them through debt, central banks are ultimately forced to monetize that debt. Even if a central bank, like the Bank of Japan today, temporarily refrains from doing so and focuses on fighting inflation, that moment will still come. Otherwise, debt sustainability comes into question. Exactly the scenario Nangle sketches with interest costs heading toward 10 percent of GDP.

The unpleasant side effect of sooner or later buying up debt through money creation is inevitable inflation. But the alternative is a complete confidence crisis in Japanese government bonds and, by extension, the entire financial system. And if you take into account that higher inflation effectively helps reduce the debt mountain (in real terms), the choice is quickly made.

I do not know when the Bank of Japan will cave, but I do know that Japan must cave at some point. That is the moment when Japanese government bonds, especially those with long duration, can briefly become attractive. Provided inflation does not first spiral completely out of control. What I also know: if interest rates are low again and inflation remains high, Japanese bonds will be a totally unattractive investment for a long, very long, time.

If a brow-furrowing chart from none other than the newspaper of the traditional financial world still does not make you think, then all I can do is wish you strength.

Jeroen Blokland analyzes striking, topical charts on the financial markets and macroeconomics. In addition, he is manager of the Blokland Smart Multi-Asset Fund, a fund that invests in equities, gold, and bitcoin.