Market sentiment in fixed income is turning quickly. Within just a few weeks, investors and even central bankers have rotated one hundred eighty degrees. Rising inflation risk and an even greater lack of fiscal discipline are pushing yields higher. It is a nightmare scenario for politicians and the run-up to a major confrontation.

Central bankers have taken another hard look at the situation. Limited government credibility when it comes to significantly reducing budget deficits, rising inflation risks, and increasing liquidity (for which they themselves are largely responsible) mean that the room for further rate cuts is limited. Some central bank members even expect the next move to be a hike.

Yields up

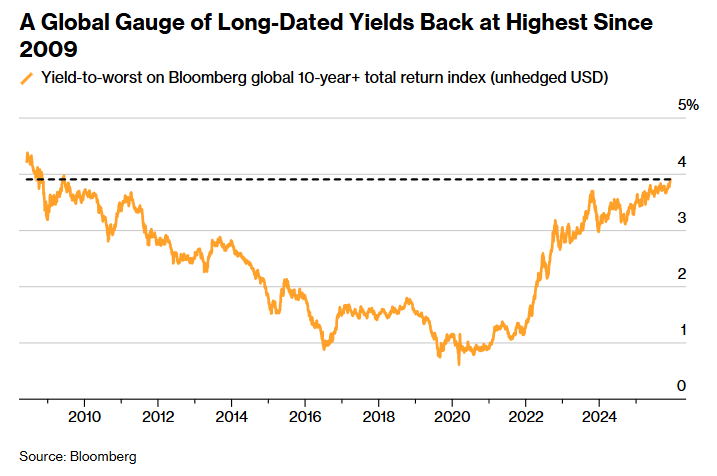

And so yields have surged in recent days, prompting flashy headlines like Bloomberg’s claim that we are now at the highest levels since the great financial crisis.

The notion that yields are “high”, however, deserves serious nuance. A more realistic view is that central banks kept yields extremely low after the crisis, even as inflation continued to rise. Add the age-old principle that more debt requires higher yields, and the resulting upward pressure should hardly be a surprise. From that same debt perspective, it is difficult to call current yields “elevated”.

Debt

With the recent rise in yields, an interesting dynamic is taking shape—one that also appeared partly in my previous column. Earlier this year, the budgets and debt levels of several countries (France, the United Kingdom, the United States) were squarely in the spotlight. Many financial journalists and market experts wrote detailed pieces on the unsustainability of those debt burdens.

What happened to those stories? Has debt accumulation stopped? No—quite the opposite. The global mountain of debt has grown rapidly again this year. Have budget deficits been closed? Certainly not. In some places the deficit is somewhat smaller, but they are nowhere near acceptable levels. Have the long-term prospects improved? On the contrary: aging populations, the geopolitical struggle for knowledge and technology, the pressing need to boost defense spending, and the persistent mismatch between mass immigration (something entirely different from targeted immigration) and the welfare state (unaffordable) are all putting even more pressure on public finances.

Conflicting interests

Budgets remain deep in the red, debt burdens were already high, and yields are rising. If the recent concerns about mounting debt have not suddenly evaporated, this seems like an impossible combination.

In France, where political bickering over the budget is a near-daily affair, interest expenses as a share of GDP are rising from 1.4 percent in 2021 to 2.5 percent in 2026. That alone locks in roughly an extra one percent of deficit. In the United States, interest expenses are heading well above 4 percent of GDP. That is more than the United States spends on defense, but also on education, infrastructure, and much more.

Collision course

The interests of governments and central banks are on a collision course—at least if you assume that monetary policy is independent and primarily focused on price stability. But why did the ecb raise rates for the first time only when inflation had already reached 8 percent? Why has the policy rate already been cut in half to 2 percent? Why are central banks preparing to increase liquidity again? With central banks, it is crucial to watch what they do, not what they say.

The solution

A brief detour to the investment industry. Asset managers are quick to capitalize on shifting dynamics. If government bonds struggle again due to rising yields and higher inflation, then you simply move to private debt—because that segment supposedly suffers less from that combination. And companies are investing heavily in the AI boom by borrowing rapidly. Would that not also become a problem if upward pressure on yields persists?

Back to the core: I would not rule out a genuine clash next year between governments and central banks, and my strong suspicion is that governments will be the ones who win.

Jeroen Blokland analyzes striking, real-time charts on financial markets and the macroeconomy. He also manages the Blokland Smart Multi-Asset Fund, a fund that invests in equities, gold, and bitcoin.