An insignificant Danish pension fund dumps all its US Treasuries. Financial media eagerly jump on this headline, because that is not something most investors would just expect. About the underlying structural cause, which has little to do with a president gone off the rails, you hear a lot less.

The Danish AkademikerPension, the pension fund for academically educated professionals, plans to sell all its US Treasuries. In the spirit of “Timing is everything,” AkademikerPension’s intention is quickly linked to the turmoil surrounding Greenland.

CIO Anders Schelde admits that these recent developments have been a factor forcing this decision. But they are not the decisive reason. That is the unsustainability of the US debt burden.

Unlike many economists, journalists, and experts, Schelde does not pin the decision on Trump. He does not improve the situation, but as Schelde puts it: once the genie is out of the bottle… In five or six years, even ten, he does not see the US national debt being fixed either.

By the way, AkademikerPension is not the only and certainly not the first pension fund to part with safe US Treasuries. In that sense, I too am engaging a bit in headline chasing.

Who will bid?

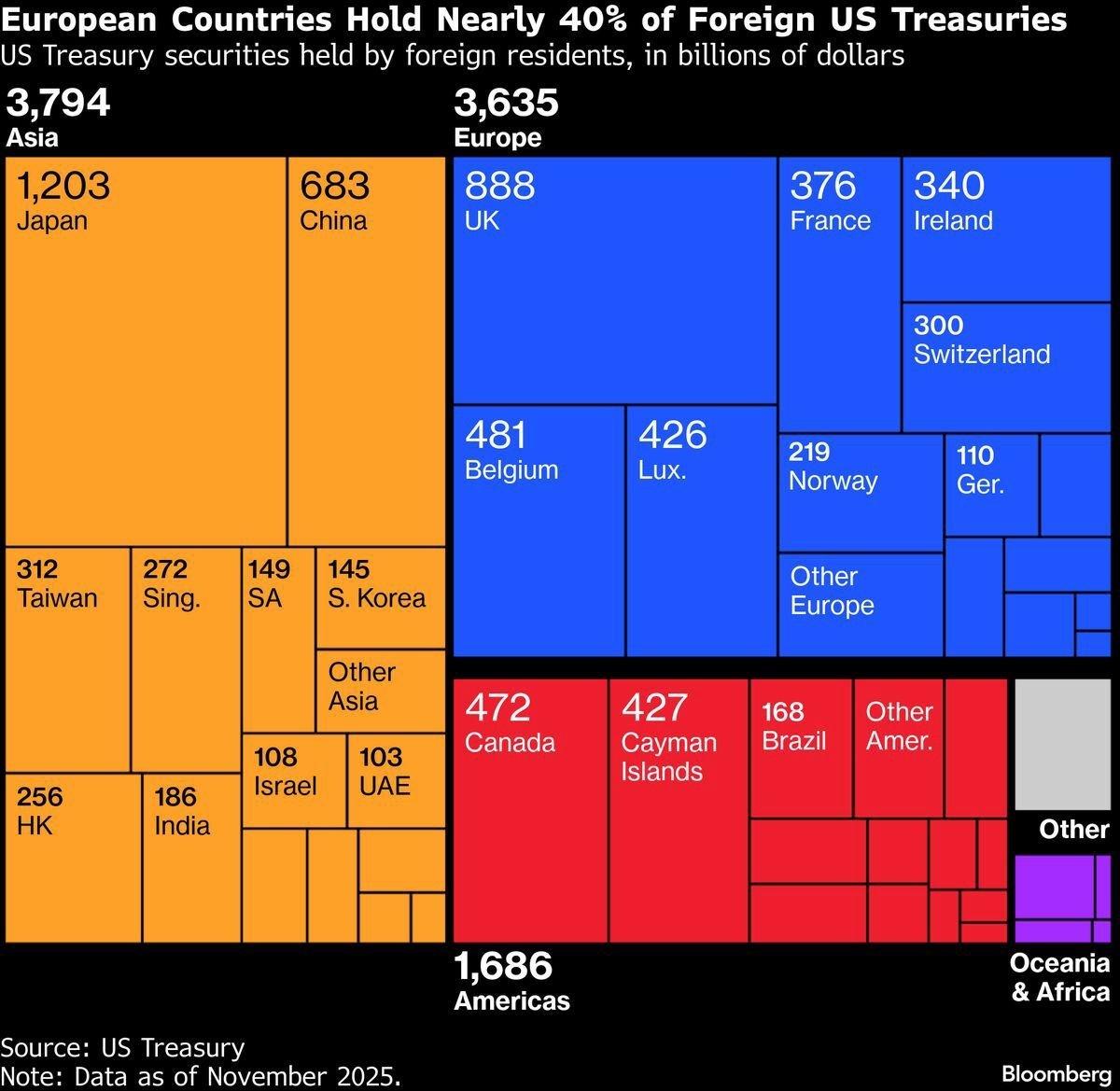

The action of a small Danish pension fund that suddenly finds itself in the spotlight brings to mind an old, still unanswered question. Who will still want to buy bonds? I have been told hundreds of times that debt is not a problem, because that debt is at the same time a fantastic asset on someone’s balance sheet.

Now it is certainly true that one person’s debt is another person’s asset; you will not hear me dispute that. But who is that someone if you conclude that US debt is unsustainable, structurally riskier than before, and probably does not protect purchasing power because inflation is higher than interest rates?

Of course, the BIS, central banks, and politicians have devised a trick by forcing financial institutions, often including pension funds, to hold (US) government bonds. For example, to meet required capital buffers. But what if foreign parties en masse conclude that US Treasuries are no longer the “ultimate” buffer material? Or what if China and Europe decide to “weaponize” their US Treasuries by dumping them on a large scale?

In the spirit of “Europe must be able to stand more on its own feet,” which is pretty much the slogan of almost every European politician these days, selling US bonds to finance European nations’ defense spending would not be out of place. It would be naive to think: that will not happen. By the way, I would prefer that financing not to take place via eurobonds, but that is another story.

The light

What I also wonder is when (traditional) investors will finally see the light. After everything we have seen in recent years, it is hard to maintain that bonds still shine as brightly as before. In just the past few years we have seen the largest bond bear market ever, the British pension sector nearly collapse after an ill-conceived tax plan, one French prime minister after another resign because of an almost impossible budget, and even the Bank of Japan was forced to abandon its bizarre yield curve control policy, with all the consequences that entailed. When I look at the price chart of Japanese long-term bonds, it looks suspiciously like 2022 elsewhere.

What if bonds have indeed become structurally riskier? What if real returns remain structurally negative? What if diversification benefits alongside equities decline en masse?

Do you then still need Trump to reach the same conclusion? Bonds deserve a much less prominent role in our portfolios.

Jeroen Blokland analyzes striking, topical charts on financial markets and macroeconomics. In addition, he is manager of the Blokland Smart Multi-Asset Fund, a fund that invests in equities, gold, and bitcoin.