With the pullback of the dollar and the decline in (short-term) interest rates this year, emerging markets have finally come back into favor. Well below the radar, however, frontier markets have already enjoyed growing popularity among a select audience for some time.

For large investors, the market is often too small. At the same time, there may be doubts about the “investment case,” or better said, the beta of this segment. Below you can see the chart showing the performance of the equity indices of MSCI World, MSCI EM, and MSCI FM.

MSCI Frontier Markets (FM) delivered an average of 5,7 percent over the past ten years, compared with 6,5 percent for emerging markets and 11,7 percent for MSCI World, including dividends. So who still wants to invest in FM?

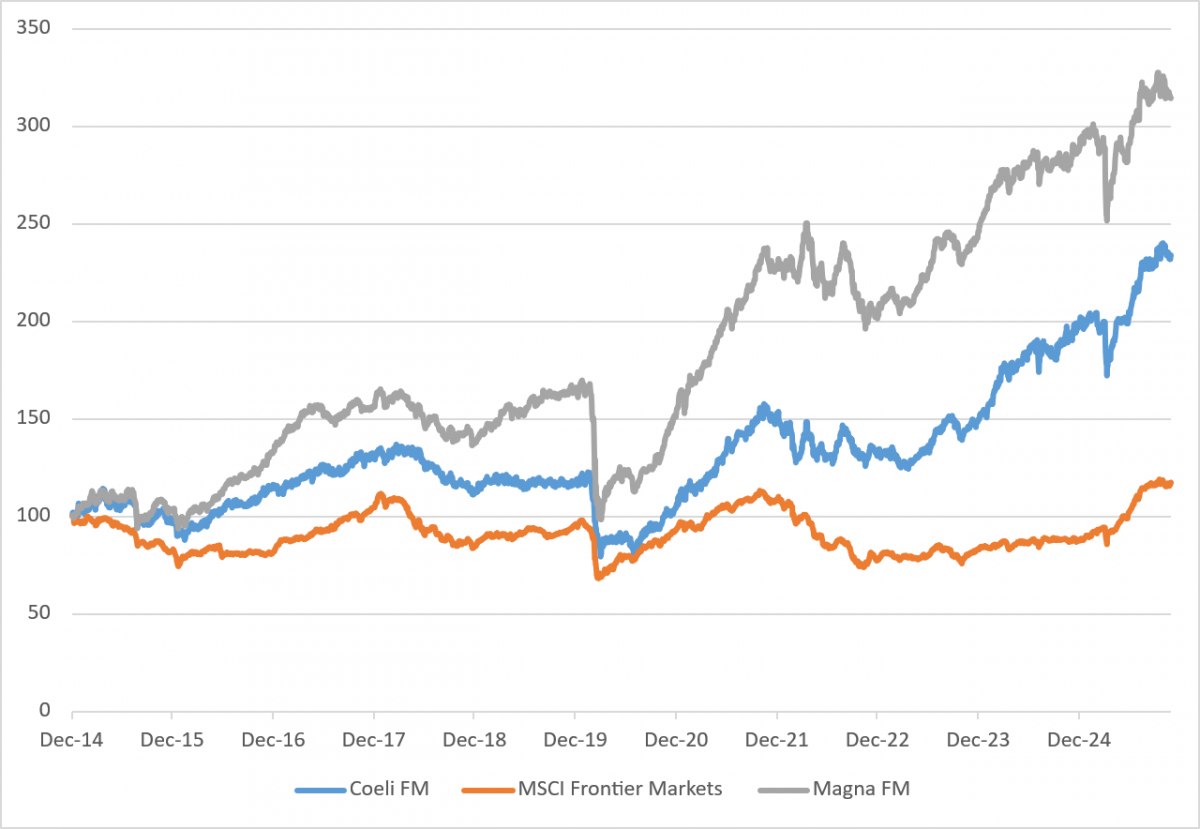

At the same time, several active managers generate annual alpha of 3, 4, or even 5 percent. Below is the net performance of Coeli and Magna, two actively managed frontier market funds: Coeli achieved 8,1 percent over the past ten years, and Magna an impressive 11,2 percent. These figures cover year-end 2014 through november 20, 2025.

What is going on here? Alpha or beta?

Source: Bloomberg.

First, the beta: it suffers from what I call “beta drift.” The composition of the MSCI Frontier Markets index changes frequently and is announced months in advance. The stocks slated for inclusion tend to rally immediately. But by the time they are actually admitted to the index, most of the performance has already been realized.

In this small universe, the active manager not only has a head start but also significant market impact. In a large benchmark like the S&P500, such announcements have far less effect. In addition, the breadth of research coverage in that market ensures that everyone sees such index inclusions coming long beforehand. Arbitrage or, more precisely, “benchmark front-running” is barely possible. EM and FM operate less efficiently, less perfectly.

An MSCI executive once told me how strongly countries lobbied to be admitted to the index. Inclusion acts as a gateway to foreign capital. I therefore view the resulting effect as a somewhat uncertain form of beta drift.

The successful IPOs that can follow from such a “promotion to FM” then become a source of alpha for the active FM manager. And to whom are those IPOs often allocated? First to domestic institutional and retail investors. But sometimes also to active fund managers who have followed the country for many years and know the local market well. Here too, the Middle East is a strong example of the extra alpha generated through IPOs. The same applied to countries like Georgia and Kazakhstan, which benefited as safe havens—also in trading terms—during the Russian war.

Another source of alpha or beta (your call) is the flexibility many FM managers have to invest outside FM, including in EM. The argument, in my view a valid one, is that you cannot predict exactly when countries like Pakistan or Bangladesh will move in or out of the index. Let alone countries such as Kenya and Nigeria. None of the managers wants to be forced to sell holdings when capital controls are suddenly imposed. In fact, when that happens, you can hardly do anything at all.

Most FM managers’ interest was directed toward Asia, where Vietnam has long accounted for 25 to 30 percent of the index. By now, that market is so developed that inclusion in the EM index appears to be only a matter of time. That still leaves plenty of countries in Southeast Asia—such as Laos and Cambodia—that could take over the baton, provided they become just as attractive an offshore alternative to China as Vietnam is today.

The most surprising non-FM addition I found in portfolios was re-emerging Greece. While those of us in Europe shunned the country for years—despite keeping it financially afloat—I noticed an FM manager loading up on Greek IPOs in recent years. And making a lot of money doing so.

So is it alpha or beta in FM land? In the end, it is mostly alpha, I think. The successful managers claim to have built portfolios with lower-than-average price-earnings ratios (around 7 to 9 times earnings) and nearly constant earnings growth of 20 to 25 percent.

At the same time, beta is artificially understated due to several forms of drift. That means this segment cannot be effectively accessed through passive strategies. Frontier markets truly require active managers.

Wouter Weijand worked in asset management from 1983 to 2025, including as (lead) portfolio manager in bonds, equities, real estate, illiquid assets, and eventually as CIO.