For decades, the search for alpha has been a quest for investors. Factor models, based on firm characteristics such as size, value, profitability, and momentum, have become the standard in every investor’s toolkit. They offer a systematic framework to harvest risk premia.

But what if these factors are merely symptoms of a deeper cause? What if the key to understanding market returns does not lie in the balance sheets of companies, but in the portfolios of the people who own them?

A recent paper, Investor Factors, poses exactly this question and offers a data-driven answer that challenges conventional wisdom. The researchers gained access to a unique dataset: the complete, anonymized stock holdings of all individual investors in Norway over a 21-year period (1997–2017). Instead of sorting stocks by their firm-level characteristics, they sorted investors by their demographic traits.

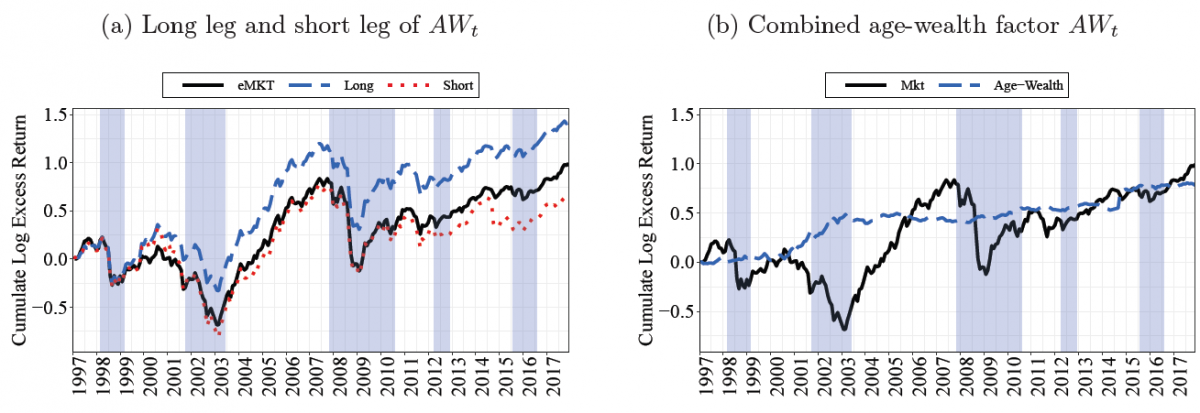

The results are striking: the researchers discovered that a significant share of the variation in stock returns can be explained by one single, powerful new factor—a long-short portfolio based on the combined age and wealth of investors. This so-called age-wealth factor goes long in the stocks favored by older, wealthier investors and short in the stocks predominantly held by younger, less wealthy investors.

This new investor factor is no academic curiosity. It generates an economically and statistically significant alpha of about 4 percent per year. This suggests that the portfolios of experienced, capital-rich investors systematically outperform.

Even more importantly, this simple two-factor model (market + the age-wealth factor) largely explains the performance of the well-known five Fama-French factors (size, value, profitability, investment, and momentum), while the reverse is not true. This implies that the investor factor may be more fundamental.

The most convincing test for any factor is its out-of-sample performance. Here too, the model shines. A strategy based on the age-wealth factor delivers an out-of-sample Sharpe ratio that is 45 percent to 65 percent higher than that of the Norwegian stock market and significantly outperforms strategies built on traditional firm-based factors. In other words, there is valuable information embedded in Norwegian investors’ portfolios.

What drives this premium?

The analysis shows that the premium is driven by a mix of rational hedging and behavioral sentiment. Younger investors, with long horizons and significant human capital, face different risk exposures and hedging needs than older, retired investors.

At the same time, younger and less wealthy investors are more prone to sentiment, often allocating to volatile, lottery-like stocks with low profitability. Older, wealthier investors, by contrast, exhibit “smarter” behavior: their portfolios consist of larger, profitable value stocks with lower volatility and lower beta (i.e., sensitivity to market movements).

For institutional investors, this research opens up a new and potentially very fruitful perspective. It suggests that existing factor premia are not merely market anomalies, but reflect the aggregated preferences, risks, and behavioral biases of the underlying investor population.

By looking directly at “who owns what,” we can tap into a more direct and fundamental source of risk premium. This approach provides a powerful, complementary perspective alongside traditional firm-based factors and may lead to more robust and better-diversified investment strategies. The future of factor investing may lie not only in analyzing assets, but above all in understanding the investor.

Gertjan Verdickt is assistant professor of finance at the University of Auckland and a columnist at Investment Officer.