A targeted educational intervention can break the free dividends fallacy among retail investors. The result: a lasting behavioral change that reveals how fragile—yet how malleable—the demand for dividends truly is.

In the financial world, Miller and Modigliani’s 1961 dividend irrelevance theory is basic knowledge: in a perfect market, it makes no difference to a company’s value whether profits are paid out as dividends or reinvested. For an investor, one euro received as a dividend is theoretically identical to one euro gained by selling a small portion of shares. Yet anyone following the markets knows reality is messier. Retail investors show a persistent, almost irrational preference for stocks with high and stable dividend payouts.

This preference is often driven by what’s known as the free dividends fallacy—the mistaken belief that dividends are a kind of free extra income, disconnected from the share price. It’s the seductive but wrong idea of being “paid to wait.” A new experiment by Hackethal, Hanspal, Hartzmark, and Bräuer dives deep into this topic and arrives at a striking yet hopeful conclusion: this deeply rooted misconception can be overcome through a surprisingly simple intervention.

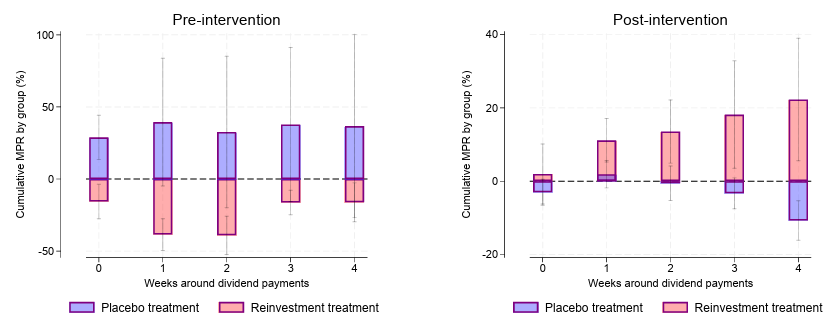

Figure: the marginal propensity to reinvest (MPR) before and after the experiment

In collaboration with a large German bank, the researchers exposed a group of investors to a brief online quiz. The quiz was designed to deliver one simple message: a dividend payment reduces the stock price by roughly the same amount, and failing to reinvest it has a dramatic negative effect on long-term returns. The impact of this simple educational nudge was then measured using the investors’ actual transaction data.

The intervention led to an immediate increase in dividend reinvestment. Investors in the treated group reinvested about 50 cent more of every euro in received dividends than before—and compared with control groups. This was not a theoretical survey response but a concrete behavioral change involving real money, demonstrating that the free dividends fallacy is a significant driver of dividend demand.

Even more remarkable was the persistence of the effect. The behavioral change was not temporary but endured across three consecutive dividend seasons. This suggests it wasn’t just a fleeting reminder, but a fundamental update to the investor’s mental model. The education stuck. Those who learned the most—the investors with the least prior knowledge—adjusted their behavior the strongest.

For investment advisors, these findings are invaluable:

- They explain market flows and pricing: retail investor demand creates dividend “clienteles” and can lead to price anomalies. This study shows that the foundation of that demand—pure ignorance—is malleable. Changes in the information environment or large-scale educational efforts by brokers can genuinely shift demand across equity segments. It’s a factor worth considering when analyzing market flows.

- They provide a blueprint for effective client communication: for wealth managers, private banks, and fund providers, this study is a masterclass in effective messaging. Broad campaigns about “financial literacy” often have limited impact. This study proves that short, targeted, and interactive interventions addressing a specific costly behavioral bias do work. It shows that clients can be helped to make better financial decisions, leading to stronger wealth growth and higher satisfaction.

This research exposes the psychological core of dividend preference. It’s not a rational choice for self-discipline but often a simple cognitive error. The good news is that this error can be corrected. For institutional players seeking to understand not only the market but also the human psyche behind it, this insight offers a strategic edge—both in market analysis and client engagement.

Gertjan Verdickt is assistant professor of finance at the University of Auckland and a columnist at Investment Officer.