For decades, it was an iron law for investors: in the long run, the stock market follows economic growth. A thriving economy translated into rising corporate profits and thus higher share prices. But anyone who has watched the past thirty years closely senses a growing friction with this old wisdom.

Markets reached record highs, while economic growth was at best moderate. How was this enormous wealth created and, more importantly, what does it mean for the future?

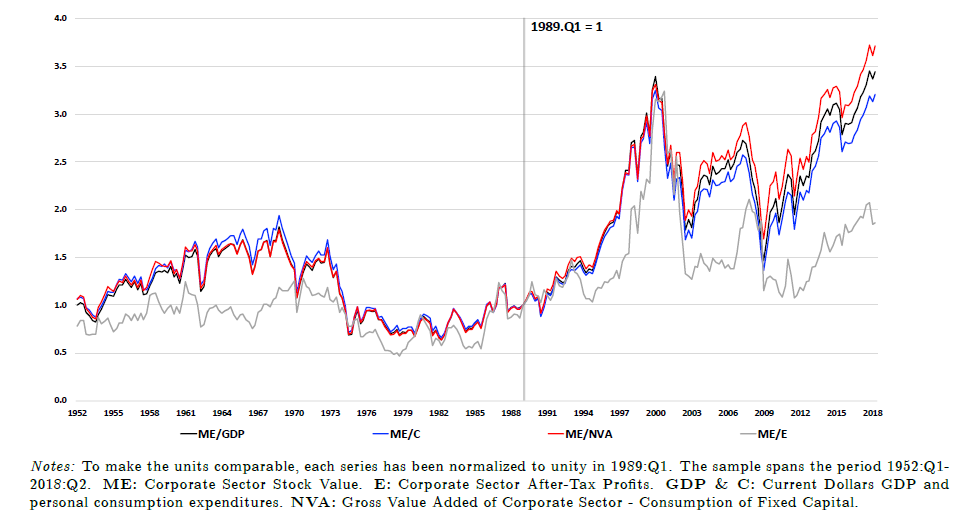

A groundbreaking 2019 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), titled How the Wealth Was Won, unravels this paradox and draws a conclusion that every institutional investor should consider. The researchers analyzed the creation of thirty-four trillion dollars in real equity value in the United States between 1989 and 2017 and quantified the underlying drivers. The results are shocking for those who still believe in the old adage.

The traditional engine, economic growth, accounted for only twenty-five percent of the value created. Lower interest rates and a declining risk premium contributed eight percent and twenty-four percent, respectively. The undisputed winner, with no less than forty-three percent of the total increase in value, was a factor often overlooked: a fundamental redistribution of economic returns, away from labor and toward capital.

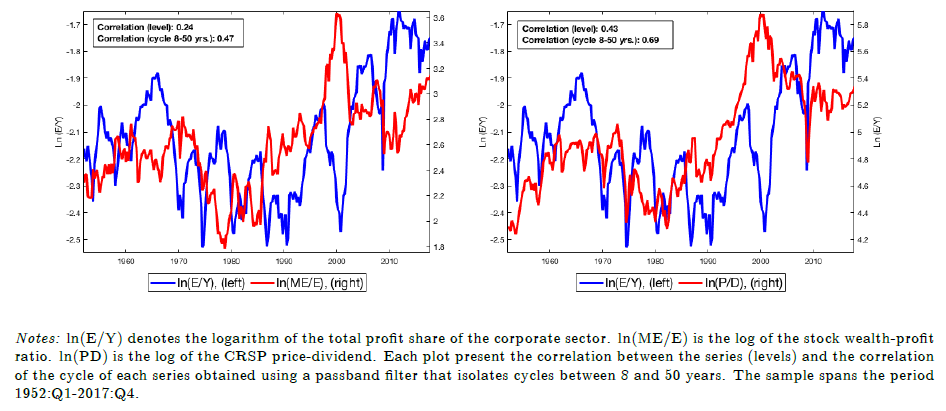

Profit share versus wage share

Put simply: the size of the economic pie grew relatively slowly, but the slice going to shareholders grew disproportionately larger. This shift in factor shares—the distribution of national income between labor (wages) and capital (profits)—is the dominant but silent force behind the bull market of the past generation. Virtually the entire increase in profit share came at the expense of compensation for labor.

This stands in stark contrast to the earlier period (1952–1988). In those years, far less wealth was created, but economic growth accounted for more than one hundred percent of the stock market’s rise. The contribution of factor shares was even negative at that time. We have witnessed a structural upheaval in the functioning of our economy and stock markets.

Labor market

What does this insight mean for strategic asset allocation? First, it forces us to reconsider the definition of fundamentals. Macro indicators such as GDP growth are no longer sufficient to understand the market. The distribution of that growth has become just as important. Analyzing the labor market, union power, globalization, and the concentration of market power in specific sectors are no longer soft factors but essential components in forecasting future returns.

Second, it has profound implications for the expected equity risk premium (ERP). A significant share of historically realized returns was not compensation for bearing risk but rather a one-off windfall from a decades-long redistribution. The study estimates that the true risk premium has therefore been overstated by about forty-four percent. Investors who extrapolate based on past returns risk systematically overestimating their future outcomes.

The crucial question for the years ahead is whether this trend is sustainable. The shift from labor to capital may have reached its limit and could even reverse under political pressure, a tighter labor market, or deglobalization. Such a reversal would mean significant headwinds for equities, even in a scenario of reasonable economic growth.

The wealth of the past decades was not primarily gained by baking a bigger economic pie but by slicing it differently. For forward-looking investors, the question is no longer how fast the economy grows, but who will receive the returns from that growth. The answer will determine tomorrow’s winners.

Gertjan Verdickt is assistant professor of Finance at the University of Auckland and a columnist at Investment Officer.