The word is out! Fed Chair Jay Powell is considering stopping the reduction of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. If you think that balance sheet has slimmed down significantly after three years of quantitative tightening, you’re mistaken. Moreover, Powell is putting himself in an impossible position once again by lowering interest rates at the same time.

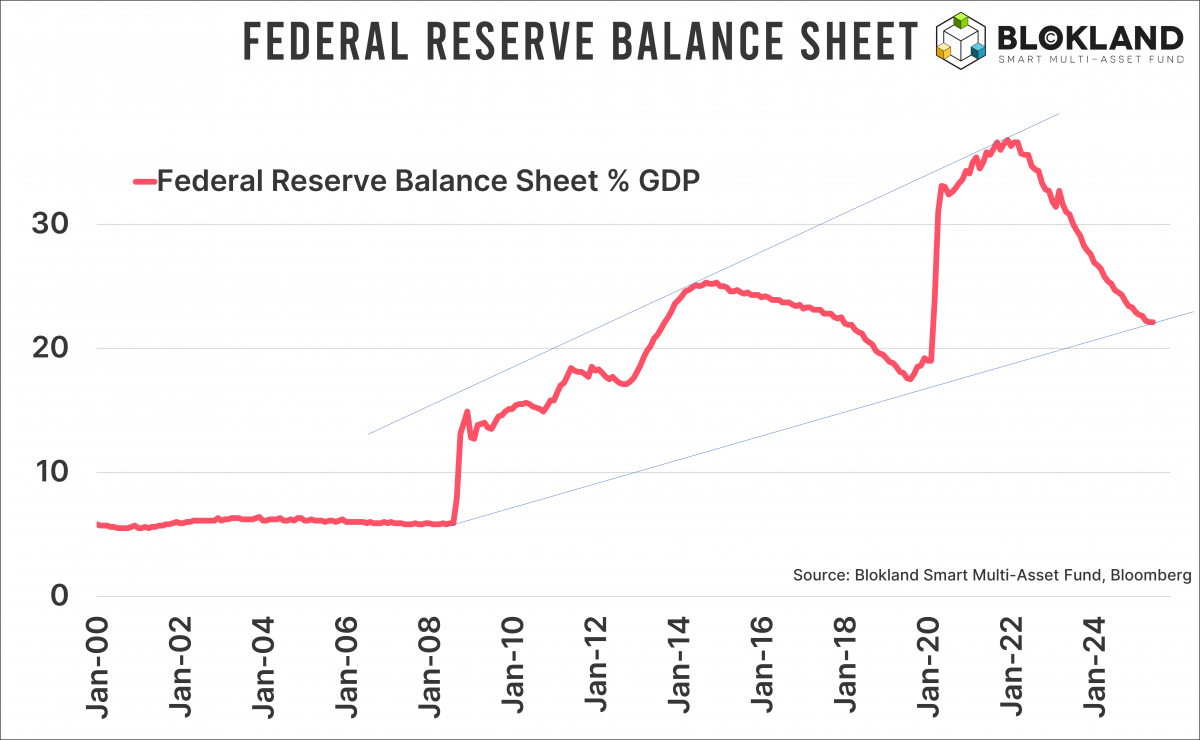

I’m certainly not a technical analyst—I never quite know where those lines are supposed to begin or end—but with just a few strokes on the chart below, it becomes clear that the Fed’s balance sheet shows an unmistakable pattern of higher lows and higher highs. A balance sheet size equal to 22 percent of US GDP is far from lightweight. And that’s no coincidence. It’s a structural feature of a system built on debt, and therefore increasingly dependent on liquidity. Powell and his colleagues openly refer to this as a necessary “ample reserves regime.”

Refinancing machine

Most major economies, including China, are no longer growth engines but relentless refinancing machines. Research by Michael Howell of CrossBorder Capital shows that the vast majority of global financial transactions revolve around refinancing. That immediately explains why debt-laden economies barely grow anymore. Refinancing—simply rolling over the existing mountain of debt—doesn’t add to GDP. At the same time, those refinancing operations require an ocean of liquidity to keep them going. If that liquidity isn’t large enough, financial markets experience immediate stress. Debt must keep rolling over.

Supersized

That is the simple but weighty reason why central bank balance sheets must continue to grow. Balance sheet policy is no longer formulated around whether inflation is under control or whether the economy can handle tightening, but around debt sustainability. Of course, Powell can now use his dual (or rather triple) mandate to point to the weakening labor market—how convenient.

Powell rejects MMT

In his speech at a National Association for Business Economics event in Philadelphia, Powell made several important remarks. He emphasized that paying interest on bank reserves is crucial for effective monetary policy. According to Powell, without this tool, the Fed would lose control over short-term interest rates.

This makes it clear that Powell considers MMT—Modern Monetary Theory—nonsense. And that the Senate was right not to approve a proposal to prohibit the Fed from paying interest on bank reserves. Such a ban would perfectly fit the MMT narrative, in which interest is merely an inconvenient side issue. Within MMT, interest rates are not the key policy instrument for sovereign governments that can print unlimited amounts of money to finance their debts and manage inflation—taxes are. Abolishing interest payments would neatly solve their problem.

I also struggle with this line of thinking. In my book The Great Rebalancing, I cite criticism from Harvard professor Greg Mankiw (known for his masterpiece Macroeconomics), who argues that interest payments on debt are simply an alternative form of borrowing. Sovereign governments can—or perhaps should—simply finance that interest. Mankiw also rightly points out that when central banks pay too little interest on bank reserves, commercial banks lend more to the economy instead. This increases the money supply, and therefore inflation risks. Yet MMT entirely depends on the absence of inflation to allow central banks to finance budget deficits.

Interest rate paradox

Powell’s argument about the importance of paying interest on bank reserves also contains a major paradox. The Fed admits that an ample reserves regime—meaning a large central bank balance sheet—is necessary for the economy to function smoothly. Yet at the same time, it continues to cut rates several more times, even though it will take years before inflation returns to target. That increases the risk that the money supply will expand further through bank lending. Especially now that the US yield curve has steepened dramatically. Whereas a year ago short-term rates (including those on bank reserves) were higher than long-term rates, the situation is now completely reversed. Banks therefore have a clear incentive to lend their money longer and at higher returns.

That means Powell—or, more likely, his successor—will once again end up in an awkward position, where the Federal Reserve claims to pursue 2 percent inflation, but in reality is chasing very different goals.

Jeroen Blokland analyzes striking and current charts on financial markets and macroeconomics. He also manages the Blokland Smart Multi-Asset Fund, a fund that invests in equities, gold, and bitcoin.