What could hardly be considered a surprise anymore still turned into one. The annual revision of US job growth came in even bigger than expected. As anticipated, it triggered a flood of reactions—though often the wrong ones.

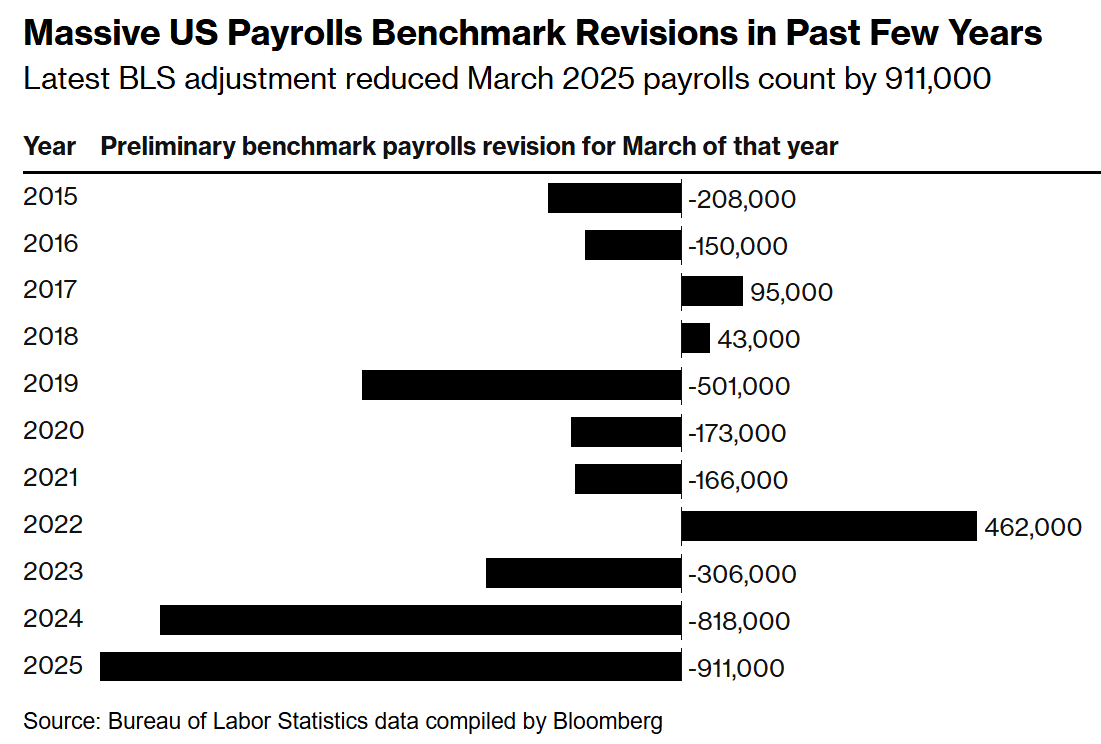

A quick rundown of the key figures. According to revisions from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, nonfarm payrolls between April 2024 and March 2025 were estimated to be 911,000 lower than previously reported. That wipes out the bulk of the assumed job growth. It was not only the largest absolute revision ever but also the largest in terms of total employment, which turned out to be 0.6 percent lower than reported.

The conclusion

The conclusion is that the Federal Reserve, both during the series of rate cuts and the period in which rates remained unchanged, consistently spoke of a resilient labor market. The reality turned out to be far less rosy.

According to estimates, the number of jobs actually shrank last year in two months—August and October. This sets off alarm bells at the NBER, the body that has the authority to declare US recessions. Employment, alongside real personal income (excluding government transfers), is the most important factor in determining a recession.

The reaction

And so recession narratives sprouted everywhere. The thrust of those stories is mainly that the Fed completely misread the situation and made the wrong decision by holding rates at 4.50 percent for so long.

I agree with the first point, but you cannot entirely blame them. They have to rely on something, even though the jobs report has already shown several times in recent years that it cannot keep up with demographic shifts. It is troubling in itself that even in the United States—supposedly the promised land of macro data—the reliability of reported figures is deteriorating.

Whether the Fed should now slash rates aggressively because job growth has all but stalled, I seriously doubt. To be clear, I think Fed officials will welcome this as a gift from the statistical heavens, because with their dual mandate they can now cheerfully cut rates. That has far more to do with debt and liquidity than with employment, but that is beside the point.

What some analysts and economists rightly note is that the so-called “silent recession” is already over. The pattern of revisions seems to suggest that the real trouble started when it became clear that the Fed would no longer cut rates.

If this turns out to be a relatively mild recession, the kind that happens from time to time, and the Fed cuts rates again while the worst of the trade-war uncertainty is behind us, then this could well mark the beginning of a new cycle. In that case, I do not immediately see a definitive end to the equity rally—unless inflation quickly flares up again, of course. Perhaps they can “revise” that downward too?

Jeroen Blokland analyzes striking, up-to-date charts on financial markets and the macroeconomy. He also manages the Blokland Smart Multi-Asset Fund, a fund that invests in stocks, gold, and bitcoin.