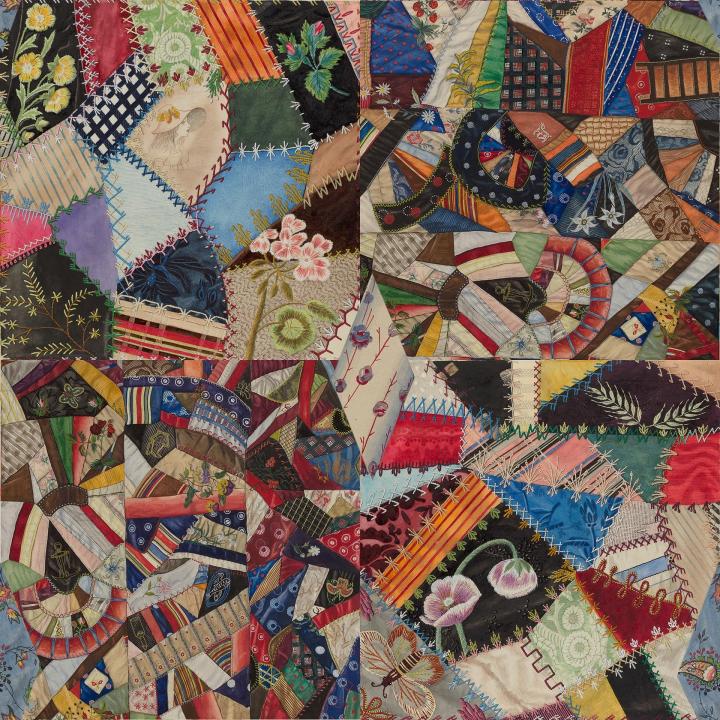

With the Dutch House of Representatives (Tweede Kamerlid) passing the Actual Return Box 3 Act last week, the Netherlands will introduce “paper gains” as a basis for taxation starting in 2028. That is entirely unique in Europe. The patchwork of solutions Europe has devised for this tax will therefore gain a new addition.

Economists generally support it, while tax advisers and their clients largely recoil from it: a wealth accrual tax, as the Netherlands will introduce from January 1, 2028, is the subject of heated debate. Marnix Veldhuijzen, tax lawyer and managing partner of Dentons in the Netherlands, was blunt in his assessment. “It seems that the Dutch House of Representatives finds it difficult to separate the pursuit of additional revenue from the need for a fair tax system,” he said in an interview with Investment Officer.

According to Veldhuijzen, the wealth accrual tax leads to “incredibly unreasonable effects,” mainly because it will no longer matter whether the taxed increase in value has been realized or unrealized. This may cause problems particularly for illiquid investments, such as those in private markets. Veldhuijzen predicted: “This new system will lead to a surge in litigation.”

The alternative is a capital gains tax, which Belgium also introduced at the beginning of this year, where it is referred to as a capital gains tax on securities. It was likewise introduced amid a flood of protests—Belgium previously had no tax on capital gains. However, the principles of the system are the same as those applied in other European countries, albeit in different forms. In that respect, the Netherlands is an outlier.

Flat rates as the norm

Investment Officer surveyed several countries to map out the various forms of taxation on capital gains and accruals*. Flat rates are the norm in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and Italy, while taxpayers in France and Portugal can choose between flat or progressive rates. In the latter case, the personal income tax rates apply. Of the ten countries in the comparison, Spain is the only one with a progressive levy for everyone. The rates are lower than those applied to labor income. That also applies to all flat rates.

This is how several European countries tax gains on stocks and bonds

Switzerland and Luxembourg are the major exceptions. Luxembourg imposes a capital gains tax only on speculative gains, defined as assets held for less than six months, while Switzerland does not tax income from wealth but instead levies a tax on total net wealth. In fact, during the initial period of the system with deemed returns, the Netherlands effectively had such a wealth tax as well. Until 2017, “everyone” paid 1.2 percent per year on total wealth, and actual income was not taxed further.

What now?

That deemed return system proved, as is well known, legally unsustainable. Since the Dutch Supreme Court prohibited the use of fictitious returns in 2021, policymakers, economists, and tax experts have grappled with the question: what now? Aart Gerritsen, associate professor at the in Rotterdam based Erasmus School of Economics, frequently participates in the debate. Last year, he wrote the scientific factsheet Een economisch perspectief op box 3 (an economic perspective on box 3). In it, he noted that there is reasonable consensus on the correctness of taxing actual returns, but also points to major disagreements when it comes to capital gains versus wealth accrual taxation.

“From an economic perspective, a wealth accrual tax is preferable to a capital gains tax,” Gerritsen says. “The tax bases do not differ—you tax the same gains—but a capital gains tax offers more opportunities for avoidance. Taxpayers can choose when to realize gains, which leads to deferral. The discounted value of the revenues then declines.”

Economists also look at “distortions,” the extent to which policy can interfere with economic mechanisms. “For example, a capital gains tax may cause investors to favor growth stocks over dividend funds or value stocks. The return on growth investments largely consists of price appreciation, which is not taxed as long as it is not realized.”

So the Netherlands has chosen the economically most favorable solution? Gerritsen: “I believe so, but that does not appear to have been the decisive argument for politicians. What was decisive is that a wealth accrual tax immediately generates tax revenues, whereas with a capital gains tax you initially collect much less during a transition period. Price gains accrued before 2028 remain untaxed, and gains over 2028 would under a capital gains tax only be taxed upon sale of the underlying asset. Under a wealth accrual tax, however, all realized and unrealized gains are taxed immediately in 2028.”

Capital gains tax for residents

This aligns with the objection Veldhuijzen of Dentons expressed earlier: the need to raise revenue has dominated the political discussion. “Box 3 has long generated 3 to 4 billion euro, and apparently it has been decided that this amount must increase,” the tax lawyer said. Data from the Ministry of Finance show that revenues have already been rising recently. Estimated revenues for 2023, 2024, and 2025 amount to 5.9, 6.9, and 8.6 billion euro, respectively.

Struggling

Veldhuijzen: “The only real reason we are now getting a wealth accrual tax is that the government needs the money and cannot wait for the payback period of a capital gains tax. We see this worldwide: governments are struggling with rising budget deficits, so more tax must be raised. Add to that that public sentiment toward wealthy individuals and entrepreneurs is not particularly favorable. That combination partly explains the renewed interest in taking further steps in taxing wealth.”

The adoption of the new law in the Netherlands is such a step. It is already clear, however, that it will not be the last. In a week, the new cabinet of D66, VVD, and CDA will take office, and in the coalition agreement of those three parties it is noted—almost in passing—that they want to further develop “the new box 3 system based on actual returns” toward “a capital gains system.” That would bring the Netherlands more in line with what is common practice in Europe.

* Disclaimer: this comparison of several European tax regimes has its limitations. To begin with, the selection of countries is arbitrary. Furthermore, the descriptions of the rate structures in the table are concise and at times somewhat simplified, without the nuances and all exceptions to the rules that the various systems contain, including, for example, loss offset provisions. With regard to the calculation example, this means that not all exemptions have been taken into account. One consequence of these limitations is that it cannot be concluded that the Netherlands has the highest tax on wealth in Europe. For example, Scandinavian countries are not included in the comparison.